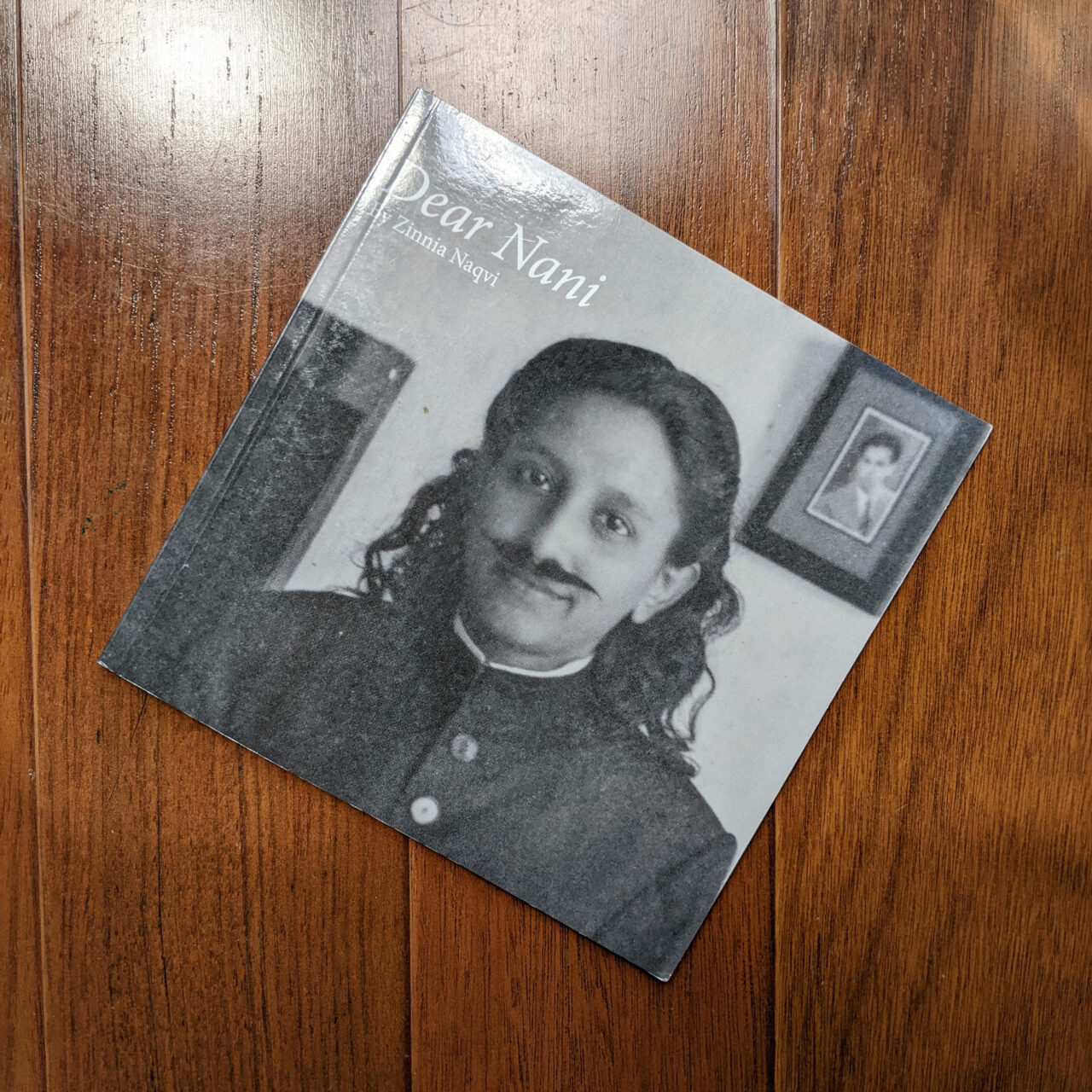

Dear Nani

Zinnia Naqvi

in conversation with

Robyn York

Published in 2022 by Anchorless Press, Dear Nani is a photobook by artist Zinnia Naqvi addressing issues of gender performance and colonial mimicry through the family archive. In this conversation, Naqvi and publisher Robyn York discuss the journey of the project from exhibition to photobook, the challenges of working through a pandemic, and funding opportunities for artists and small publishers.

ROBYN YORK When I saw your book at the CONTACT Book Dummy Reviews in 2019, I was really impressed by how well-developed it was. It was clearly something you cared about and I could see the excitement and interest that you had about the project. It seemed like it was fairly far along the path to becoming a book, but you were also thinking of it in terms of exhibition. At what point did you start thinking about presenting it into a book?

ZINNIA NAQVI I saw the project as a book not from the beginning, but from the first time I exhibited it. Almost all of the times that I’ve shown Dear Nani in an exhibition, I’ve never actually been able to show the full breadth of the work. It is a very dense project. I also see it in a linear way, because it does have this narrative that threads throughout the images. At the beginning, I start to ask some personal questions and then by the end I say, “I wish I had asked you this, but I wasn’t able to.” I reveal that the text is also fictional at the end. So it made sense as a book.

For the Reviews I had just made this little Blurb copy, and I was trying to translate what I had done in exhibition format to a book, but I was struggling with that. I’d never made a photobook before and there are so many different materials. The Reviews were really good for me because I got a lot of honest feedback, which I actually think is rare at these kinds of events.

RY I agree. It often feels sort of *mimics quickly flipping through a book* oh, nice, then people keep moving and don’t really give you any feedback, which can be really frustrating.

ZN Yeah, it was very eye-opening. When people see the work in person, I think, generally they’re pretty drawn to it, but people were not that drawn to the book I made (laughs). It showed me that, oh, the way I had done it in a gallery is not translating to the book.

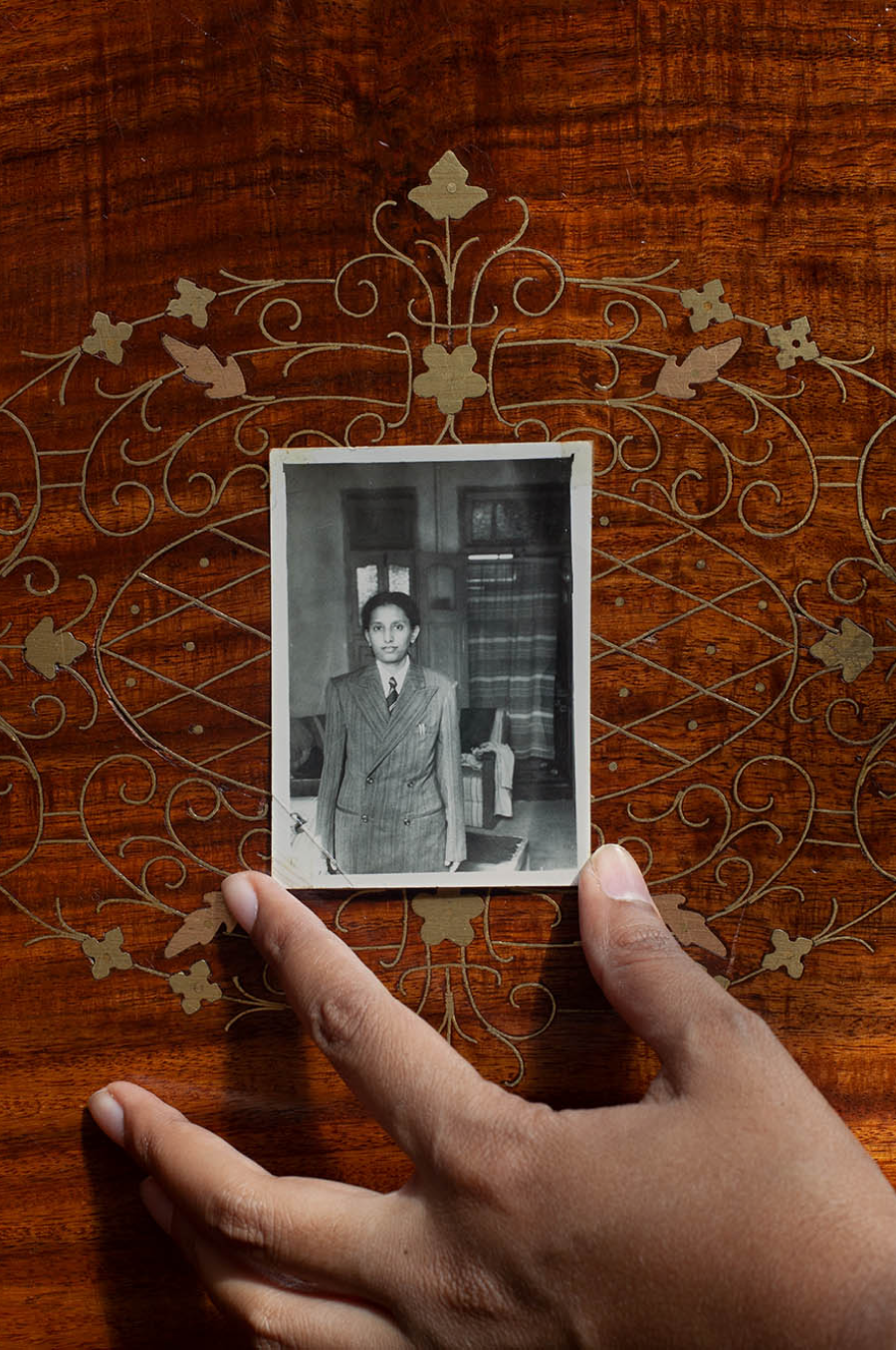

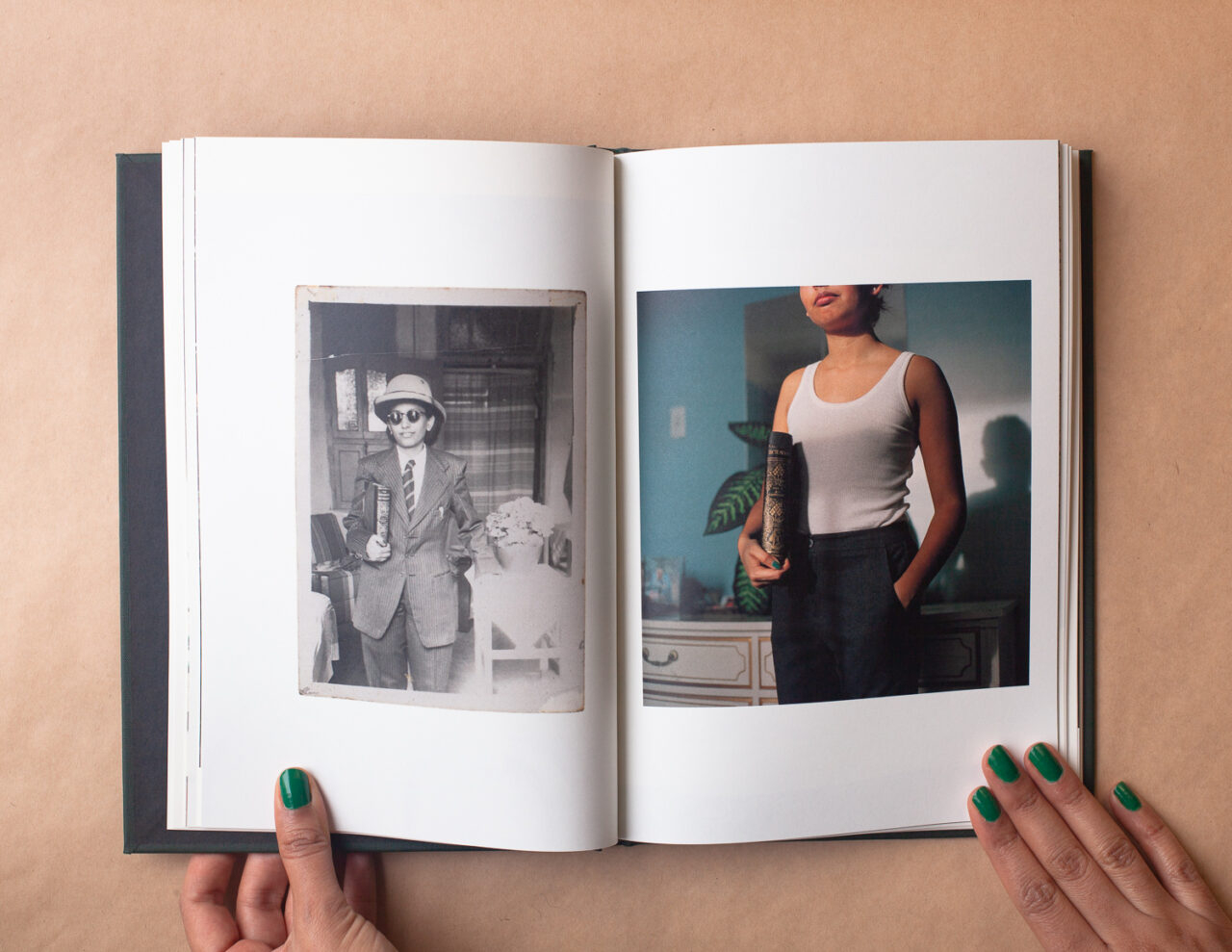

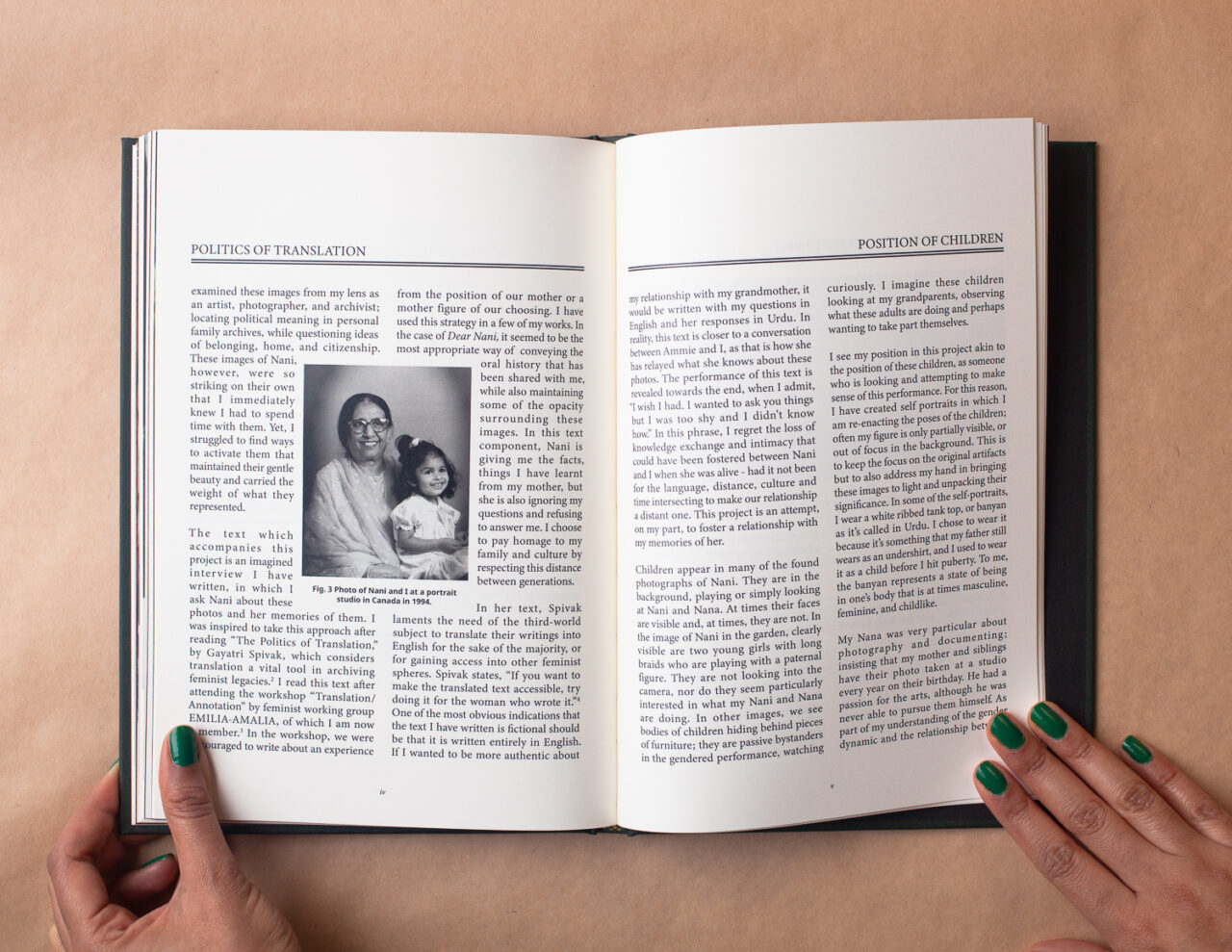

Because I’m working with archival images, I had included scans and reproductions in the book. When I show them in an exhibition, you can see the actual physical photograph. But in the book, people just thought they were Photoshopped because they were flat and didn’t have the same physicality and presence. It hadn’t occurred to me that I needed to make it clear that these are physical objects. So that feedback actually sparked me to shoot new images in 2020 that are included in the book, more of me actually holding the photos with my hands and things like that.

RY I remember you having big prints at the Reviews, but I don’t even remember the Blurb book that you had, which is really funny.

ZN Yeah, I still have it here somewhere. It doesn’t do the project justice, but I had no clue how to select paper, and how to think about covers, and just the physicality of the book. All of those wonderful things that you helped me with! I had some pretty specific ideas in terms of design, but at the end of the day, I’m not a designer and I really needed a professional. That’s why it was so great to work with you and also with Adam Simms. There’s a lot of me in the design, but he was able to take it to that level where it all made sense cohesively and did what I wanted it to do. I really needed that help!

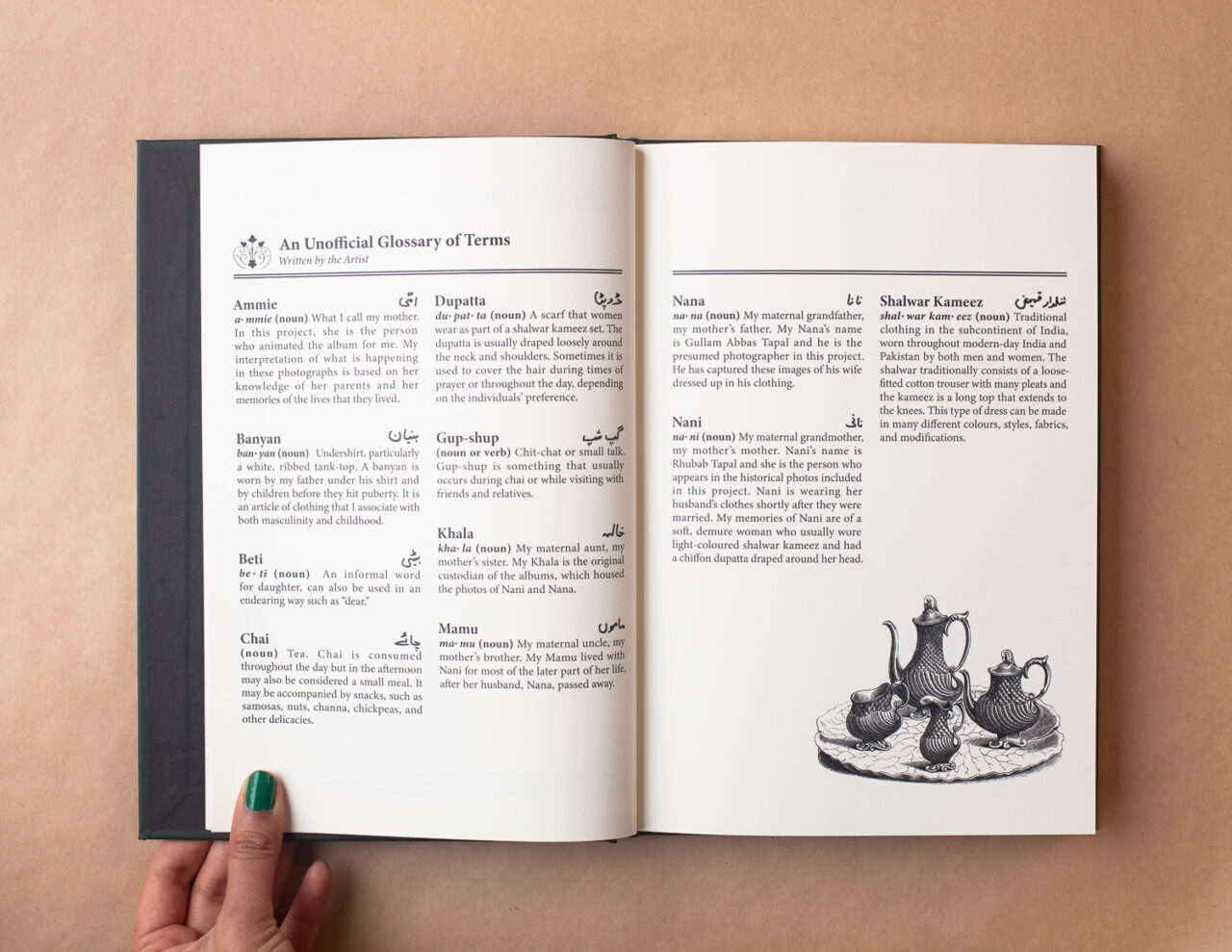

RY This was the first one of the first books where I haven’t helped with the design too much, I was much more in the publisher role of helping put all the pieces together. I think you and Adam worked well together; you can see it in the way you were able to reproduce the look of that encyclopedia in your text and your own chapter titling.

ZN Even though Adam and I were both in [Montreal], we were working remotely almost the whole time, so that was difficult. But he said, okay, this essay needs to feel like the dictionary, because it is such a specific early 20th-century design style, and so I sent him reference photos, and he used those as the design inspiration for other parts of the book too. Those kinds of impulses were really strong and I think brought the book together.

RY It was tricky working virtually, because we thought we’d have more time to work together and look at samples. We did a lot of that just over Zoom, holding a book up, or through Google chat where you’d send me pictures that you saw at Anteism.

ZN I wish I could have done more physical research, COVID really was a hindrance to all that. I really have no idea how we made such a beautiful thing.

RY Was there anything else in the process of making this book that you were really surprised by?

ZN I guess I would be curious as to how you do this normally, if there even is a “normal” way. Maybe it’s different every time to make a book? Making a book that is such a personal project and uses really personal artifacts, even though I think it did come out that way, it felt very distant from me until it was made. I think because you and Adam were so professional and knew what you were doing, it came together so well. I’m still surprised at how beautiful it is. It’s actually kind of mind-blowing!

RY There is this big leap of faith every time I make a book. I find there’s this moment where you’re looking at all the different printers and options and you’re trying to decide on certain things, and eventually you have to settle on them. And then you send off your deposit and all the final files and it’s out of your hands. Then you get this box of books delivered to you, and hopefully they’re what you imagined them to be.

This one, I was surprised in the best way when I got to see it finally. I mean, I was expecting it to be really beautiful, but the color reproductions are so good, and being able to work with printers that do the Smyth sewn binding was amazing because I hadn’t been able to do that affordably before.

ZN Maybe that would be a good thing to talk about since a lot of people have been asking me, “How did you afford to work with Flash [Reproductions]?”

RY We did a run of 100 English and 75 French, which is a really small run, especially because it’s really two books. I was surprised that they would do that small of a run with Smyth sewing because usually it’s 350 to 500 copies, minimum. I think [Flash] just got new equipment in the last year or two and they’re trying to do more artist books in small runs, which is cool. But there’s a lot of fundraising or grant writing that needs to go into getting enough funds for the production, that’s also a big part of it.

ZN What made you want to publish Dear Nani under Anchorless Press?

RY Personal and biographical projects really interest me, and I think they’re really well-suited for books, because you’re looking at them in your lap, they’re small, they’re contained. It’s a one-person experience when you’re looking at an artist book. That story felt very much like it needed to be a one-on-one story since it’s a one-on-one conversation that you’re having through the book.

I really liked that you are tackling gender play in photos from 1948. I thought it was really exciting that you found these family documents that have such playful exploration and performance. I think it resonates across a lot of different ages and demographics because of that.

ZN You know, a couple of people have come up since I made the project and said, “Oh, I have photos of my grandmother in India where she’s doing the same thing.” And even looking at The Image Centre, they recently had the Mauvais Genre exhibition, and it’s all from the early 20th century. It’s interesting because there are different people cross-dressing for different reasons. I brought my class to see it, and it’s interesting to think about our memories of the past. They’re often a lot more conservative than things actually were. When it comes to cultural trends or gender norms there’s an ebb and flow, and it’s sometimes the more recent past that pushed conservative values.

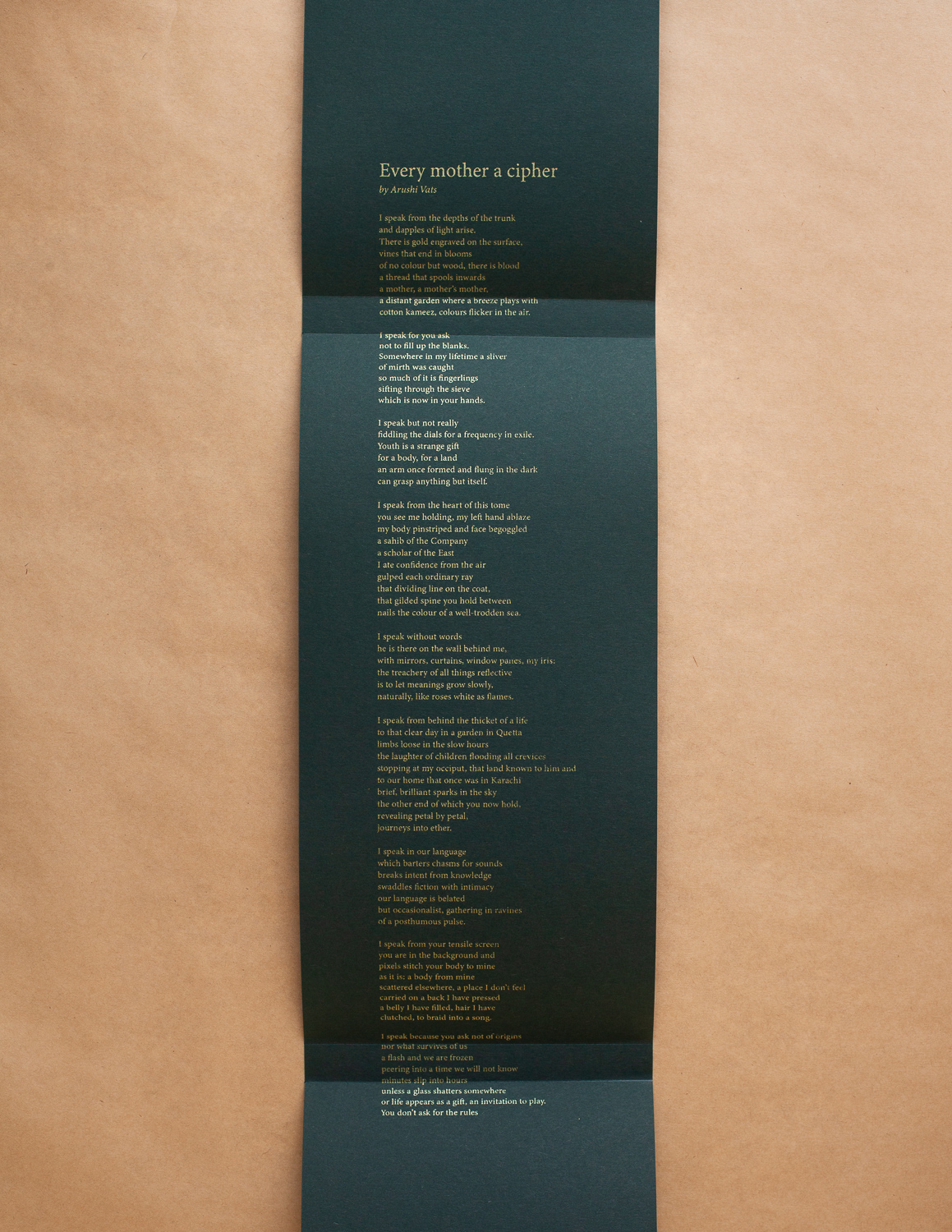

I wanted to keep that in mind with this book, and that was why it was really important for me to write my own essay at the end. It’s a very specific history that’s related to gender play and also to colonialism and independence. I wanted all of those things to intersect and I felt like it was really important for that to come from me. I had those ideas in my head for a long time, and I wanted to get them out and I was really happy with the opportunity to have them included in the book.

RY Yeah, I think it really gives a lot to the story and to the book. My reading and why I wanted to publish this book is very much a personal thing, and it’s only a tiny slice of the whole story of your book. That’s what I love about photobooks as an art form: we all get to have our own reading and our own reason for appreciating them. It’s very similar to standing in front of an artwork, you don’t get the same experience from it that someone next to you does.

ZN Just to add to that, too, is the archival nature of books. I mean, obviously it’s kind of implicit in the form but exhibitions come down, right? But whoever has this book, they’re able to hold on to it, return to it, and then also to have the project preserved. A lot of my family members have the book now, especially my mom’s family, so now all of their kids will have it. A couple of my cousins bought two copies and they’re like, “I’m going to save it for my kid too!” It’s become this heirloom where history can live on.

I was actually having a conversation with my cousin who lived with my Nani, because I didn’t know her super well and she and my other cousins lived with her until they were teenagers. We have really different recollections of her, so we were comparing notes and she said it was really interesting to read my essay because they had a completely different impression of [Nani]. Sometimes you can live with someone like your whole childhood and you don’t really know them. It’s sparking a lot of nice conversations.

RY Has this process changed how you look at visual books or photobooks?

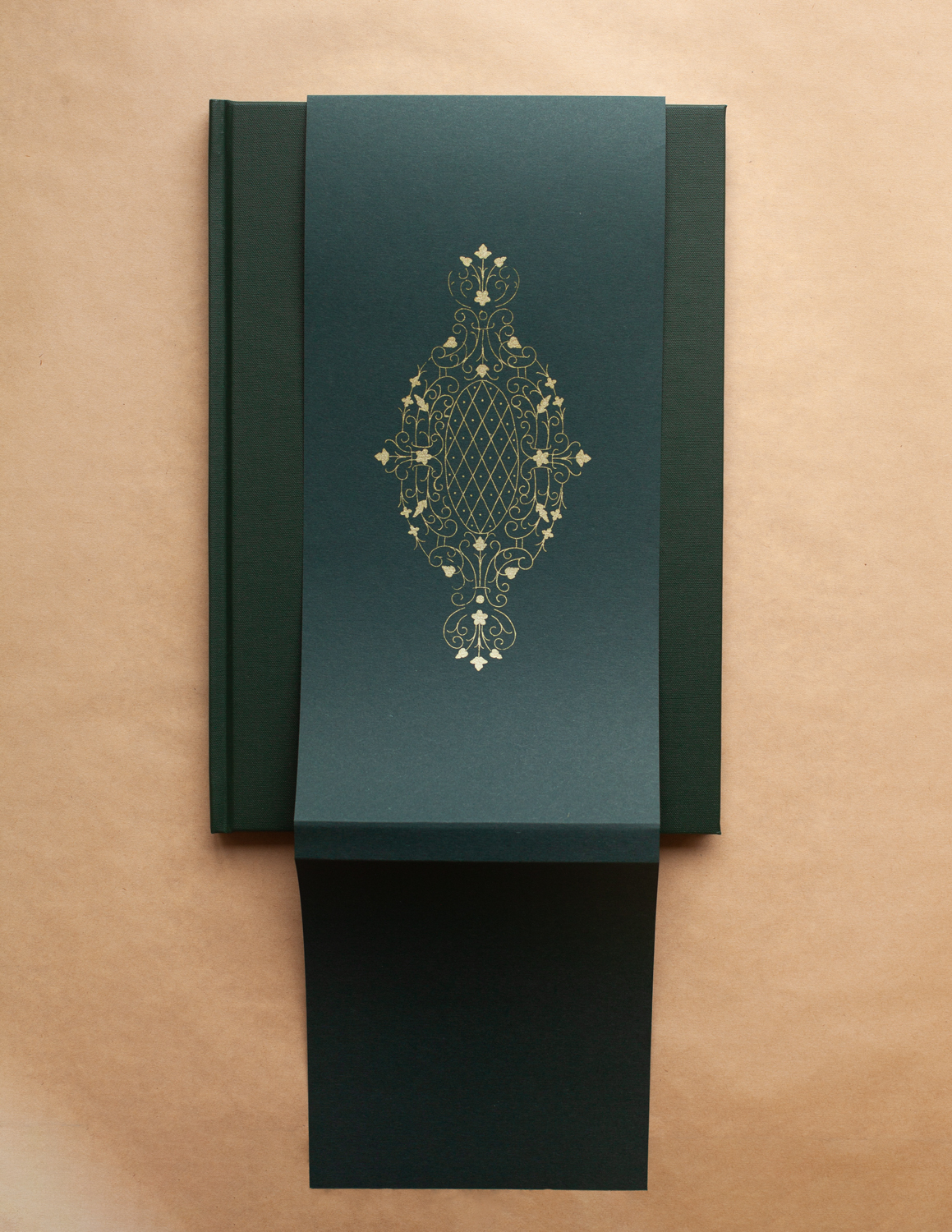

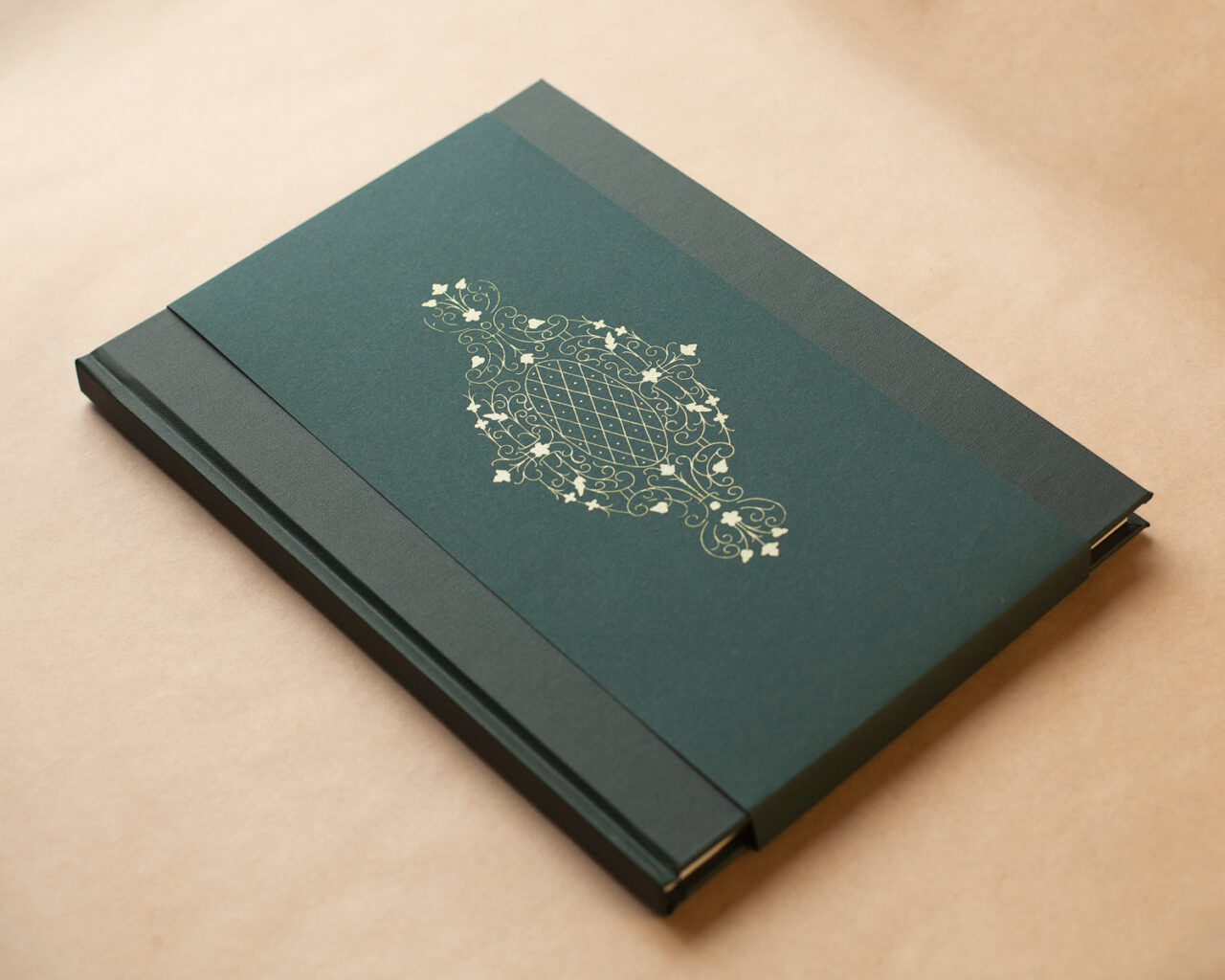

ZN Oh, for sure. I did value books before, but I can now better see the potential for them as artworks and also as a way to preserve artworks, too. Sometimes you can’t always go see an exhibition in person, but a book can go anywhere in the world, and that’s really exciting. I’ve also been appreciating the little details, the handmade elements. That was something that you wrote into the grant and really made sure that we factored in, and I think that just brings the whole book to a whole new level. I probably wouldn’t have thought to prioritize that otherwise, and out of that idea came the book jacket cover and I think that makes it such a more rich and unique object. It’s intricate in a way that’s quite striking to people as soon as they see the book.

Some other very precise feedback I got at the Reviews, actually, was, “Don’t put a photo on the cover. Don’t give it away.” Because there’s this idea of secrecy. You want to be able to open the book and find out more. That’s when I thought of the design and then, you know, opening the trunk and we wanted some more graphic elements too. All of these things were already around me, it was just a matter of looking more closely. So that was really great.

RY It feels very organic that the band has to be opened to get into the book, because the trunk that you’re photographing has to be opened to get into the stuff you found.

ZN In terms of Anchorless Press, maybe it would be nice to give a bit of a trajectory of how it started and where it’s going.

RY When I started in 2011, I really was just helping people self-publish their work. I wasn’t thinking of actually having my own publishing imprint or mandate as being important. I did that for maybe two or three years, and I did a lot of different projects that were too varied when I look back at them.

ZN So you were kind of a consultant?

RY Kind of, yeah. Or Anchorless was just an umbrella for people that didn’t want to self-publish. But it didn’t have its own identity. Then I started working at Gallery 44 and getting more involved with the photo scene in Toronto, and working with a lot of different photo artists who are making these really great photobooks. They were doing really small runs of things, you know, 25 or 50 or something like that. So that started to form what I was more excited about Anchorless Press.

I started off studying photography and then I started making my own books in school and then I went and studied photobooks, specifically in Rochester at the Visual Studies Workshop, so that was always the area that I was most excited about. It organically grew into that identity. And then I took a bit of time off raising my kids, but I sort of kept projects going in the background.

Dear Nani is actually the first of two books that we’re doing with a Canada Council grant. Writing that grant gave me renewed excitement about publishing and supporting more artists that need help with resources. Having some money to help with production costs can help change a book a lot. It helps make the book you want rather than the book that you cut corners on to try and make it fit the budget.

ZN Totally. I feel like we didn’t cut any corners.

When we wrote this grant you had an emphasis on wanting to support photo projects by women. When did you start thinking about that?

RY I was really thinking about that after the Book Dummy Reviews that we both attended, where we renewed our friendship. I looked around the room, and all of the tables with male artists had people talking to them, and all of the tables with women artists didn’t. There was just this really weird divide and I said, well, I’ll go visit the women here. And I looked at 30 or so amazing projects. All of them at different stages, all of them that could benefit from funding and mentorship. Some of them were almost a fully realized project that needed some kind of institutional support.

The other thing that came up that weekend in 2019 was the Women in Photobooks symposium that CONTACT hosted. Delphine Bedel gave a really amazing artist talk about how women have been making photobooks since Anna Atkins. We have a strong, long history of it, but there hasn’t been as much of a focus on it, because it’s on Robert Frank and Lee Friedlander and all the old dudes. That may really be behind my urgency in finding money and making that part of my mandate, rather than just saying, “I’m going to publish everything.”

ZN It’s important to figure out—what kind of space you want to fill.

RY I think you and I actually talked about funding that weekend because it was like, “This is great, what do we do now?” I left thinking I just need to find money to help make these books. So that’s when I started doing some research, and the Canada Council for the Arts added Visual Arts Publishers to their project grants stream a few years ago. When I started Anchorless, I looked into how the publishing stream worked and it’s super rigid. You had to publish a certain number of books with a certain number of pages. For a small, self-funded publisher it was impossible to reach those standards. Sometimes an artist’s book can be 10 pages! It was very restrictive. I feel like your project is a really great success because of the support of this new grant stream.

ZN Absolutely. It’s maybe more competitive, but it’s great that there’s this stream that is more accessible for artists now.

So what about you? Kate Hutchinson’s book is coming up next. Do you have any ideas for after that?

RY I’m going to take a little bit of a break, because I’m just processing family stuff and possibly opening a bookstore in Port Dover if we get a space. I’m hoping to have a workshop space there because I have accumulated all of these interesting tools for making books like a guillotine and a perfect binder

I’m hoping to work with Judy Ruzylo who has this amazing book about following a sheep herder in his 80s. I met her at the Book Dummy Reviews too, and she had the book pretty much done at that point. It’s this really simple, slow story about traveling. She’s just walking with this shepherd and having a conversation with him in broken English. Once we find money for that we’ll work on that project. There’s a couple other ones that I’m really excited about that aren’t confirmed yet. What are you working on next?

ZN I haven’t fully started yet, but for a while I’ve actually been wanting to look at the dictionaries that are in the book on their own as another project. They’re such interesting and problematic books, but they’re also so beautiful. I actually went to London in 2019 and did some research and there’s a parallel set of dictionaries housed at the British Library, but they also have them here in Toronto. The dictionaries I have in my family home were printed in India, Burma and Ceylon, but there was another set I found called the Waverley Children’s Dictionary that was printed in London. They’re almost identical but I want to compare and contrast and photograph them.

Also, now that the book is out there and we are almost sold out, I’m starting to think about printing more.

RY I remember we talked about how big to do the first edition, and we thought, let’s make it manageable because we were doing the handmade element and didn’t really know what that was going to be like.

ZN I want them to go to so many more places! I’d really like to get it more into India and Pakistan, because I think it is an important project and it’s a good way to have people there be able to access it as well.

Dear Nani/Chere Nani is available to purchase in limited quantities from the Anchorless Press online store, the CONTACT Photobook Lab, and at Art Metropole in Toronto. A special edition with a fine art print is also available online.

Visit Art Metropole on August 20 for a drop-in signing of Dear Nani from 2-4pm. The event will take place outdoors, and refreshments will be provided.