Nathaniel Brunt #shaheed

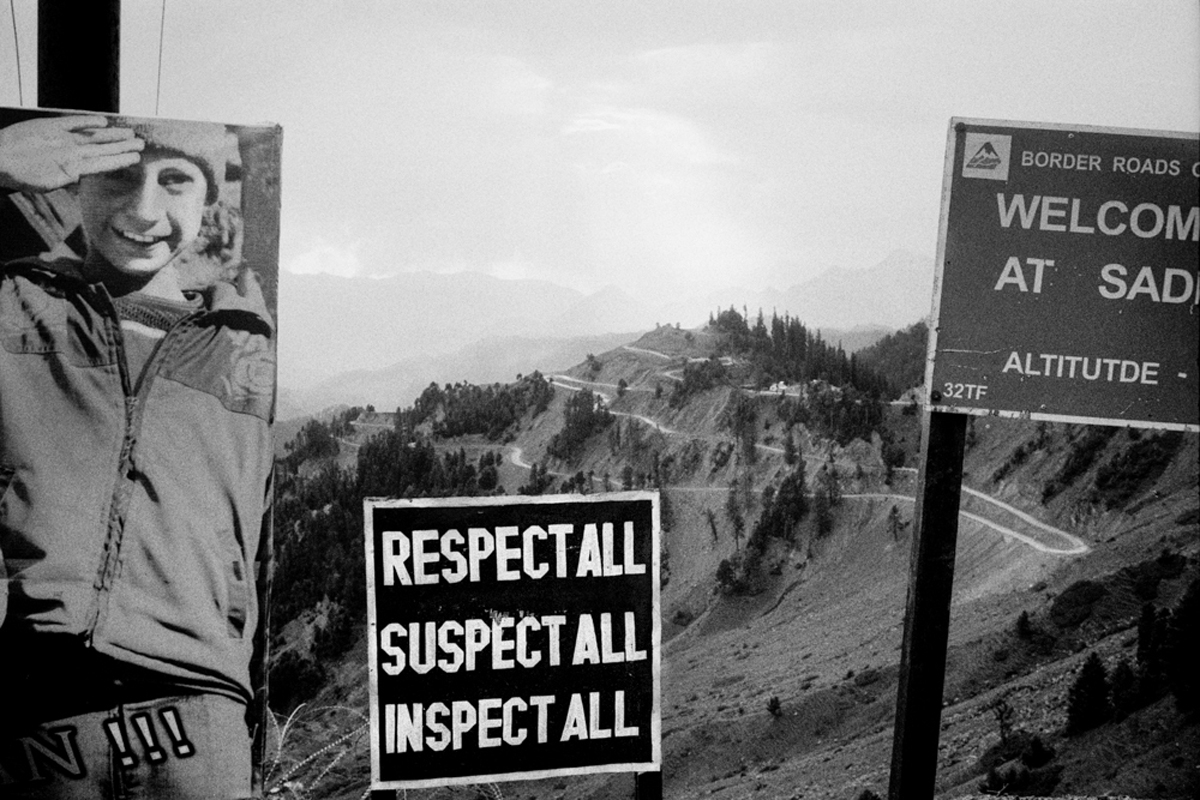

#shaheed explores the evolution of photojournalism and its current role in documenting conflict, while seeking to visually unpack the complex war in the Kashmir Valley. The exhibition is comprised of black-and-white photographs taken in the region by Canadian photographer Nathaniel Brunt, and nearly two hundred colour images and videos that Brunt was given by Kashmiri families and that he collected online from social media. Brunt travelled to the region multiple times between 2013 and 2016 and documented its violent conflict and the affected society with his Leica and Mamiya cameras. On his first visit, Brunt took a traditional approach to photojournalism, documenting events such as street protests and funerals as truthfully as possible, trying to visually make sense of them in order to have his photographs published in a magazine or newspaper. However, he found that his images inevitably seemed, in his words, an “oversimplified representation of a region and conflict that was not my own.” How could one photographically represent the intricacies of such an increasingly complicated, ongoing war without turning it into a reductive narrative?

The war in the Valley stems from a long-standing dispute between India and Pakistan, who have been vying for control over the region since Indian independence in 1947. At that time the area was under Indian control but had some autonomy, and the internal politics of Kashmir were relatively peaceful. However, by the late 1980s controversial state elections led to widespread disillusionment with the Indian government, causing Kashmiris to protest, some looking for union with Pakistan while others wanted full independence. Indian armed forces reacted violently, spawning a full-scale independence movement and insurgency. Pakistan provided Kashmiri separatist groups with support and training. As the conflict wore on, the struggle gave way to conservative Islamic agendas when many foreign fighters started to come across the border from Pakistan, prompting Indian armed forces to continue their violent efforts. This climate of brutality led to the dissipation of the Valley’s social fabric and rich tourism industry. A generation of young Kashmiris came of age during this time and many, mostly men, chose to join militant organizations to counter the oppressive fear and powerlessness that had dominated their lives. However, the fate of these men was and is often one of martyrdom, or shaheed in Arabic.

Upon subsequent visits to the Valley, Brunt began to investigate its visual history, collecting vernacular photographs from archives, portrait studios, and family collections. He continued this work into 2014, which saw a rise in the number of Kashmiri men joining militant groups. Using their mobile phone cameras, these young recruits took to social media to share photographs of their daily lives as they worked to “liberate” Kashmir. Brunt began collecting these images and videos by searching online with the hashtag #shaheed, recognizing that they provided unprecedented insight into how the militants see themselves, and how they want to be seen. In contrast to more traditional photojournalism consisting of imagery taken by an outsider who oftentimes tries to emulate photojournalistic tropes, the photographs created by these young men are intimate, poignant and often harrowing attempts to articulate personal identity in the face of violence.

What is the photojournalist’s role in an age of social media and instant image circulation? The images created and shared by the soldiers depict the close bonds they have with one another, and also show the wounded, the grieving, and the dead. Funerals in the Kashmir Valley, a tragically common occurrence, are attended by thousands and are hyper-photographed. As Brunt says: “Images of the shaheed’s corpse, which is the dominant photographic interest, are created as visual memorials of heroic sacrifice and as a traditional mnemonic document of the individual’s life and deeds.” These images circulate online via myriad social media and image sharing platforms, celebrating and honouring the dead. Such heroism is also evident in the militants’ own images of themselves. Thousands of photographs exist of the men posing with guns and rifles, presenting themselves in a sort of glamourized militancy. Others, including selfies, are adorned with what appear to be teen pop illustrations such as hearts and flowers, or are heavily filtered to create a feeling of other-worldliness and invincibility, while also being funny and enigmatic. Other photographs and videos depict everyday events, from celebrations and shared meals to naps and downtime—even the simple and satisfactory act of gathering to break open a watermelon on a hot day. Much of the imagery that Brunt found online was incredibly propagandistic, but it was these photos and videos made by the Kashmiri militants, with their combination of playful affect, daily routine, and deadly struggle, that he was drawn to, and that speak most clearly to the power of online image circulation.

Acknowledging the contested role of the photojournalist in our post-truth era, Brunt exhibits these varied forms of photography and video together, thereby expanding his role from photographer to collector and archivist. His black-and-white photographs are placed in a traditional linear narrative along the gallery walls, which is then abundantly disrupted by the plethora of collected imagery. The adjacency of the images gives viewers the opportunity to see multiple subjectivities at play and to discover more nuanced connections, while their gallery placement speaks to the enormous quantity of images created and shared online daily. By including photographs created by non-professionals who are actively and intimately involved in the Valley’s conflict, he steps away from the hierarchical distribution of photojournalism’s past, inviting a much more progressive and horizontal manner of contextualization and visual storytelling.

Curated by Heather Rigg