Group Exhibition An unassailable and monumental dignity

- Alexandra Bell

- Mohamed Bourouissa

- Leslie Hewitt

- Aaron Jones

- Keisha Scarville

An unassailable and monumental dignity explores images of black males in the public sphere. Artists Alexandra Bell, Mohamed Bourouissa, Leslie Hewitt, Aaron Jones and Keisha Scarville use found objects and photographs to question the contexts and truth claims found within them. What are the intersecting forces that place photographic images of black males in public spaces? What are the photographs intended reception? Most often they are transmitted from a place that espouses white supremacy and racial bias through the continued use of negative, dehumanizing visuals. Enacting agency through intervention and recontextualization, the artists liberate such objects from their entrenchment within oppressive power dynamics.

Mohamed Bourouissa’s Shoplifters series (2014 – 2015) is based on Polaroids that depict men who were caught stealing items from a Brooklyn grocery store. The Polaroids were placed within the public space of the store, visually indexing the almost exclusively black, male perpetrators as guilty criminals, positing an archive akin to police profiles. What do we know about these people, and what are the larger forces affecting their lives that led to their need to steal such basic food items? Brooklyn is, after all, a rapidly gentrifying borough, leaving many residents further marginalized through increased economic disparity, limited employment opportunities, and the rising costs of living and housing. When Bourouissa came across the photographs they were worn and looked abused. Through restoration efforts and formal framing, Bourouissa transforms the criminalizing snapshots into dignified portraits, resisting the axes of racial, social and economic division that they originally reinforced. The complex objects beg further questions regarding the modes of resistance the men offer by allowing their photographs to be taken.

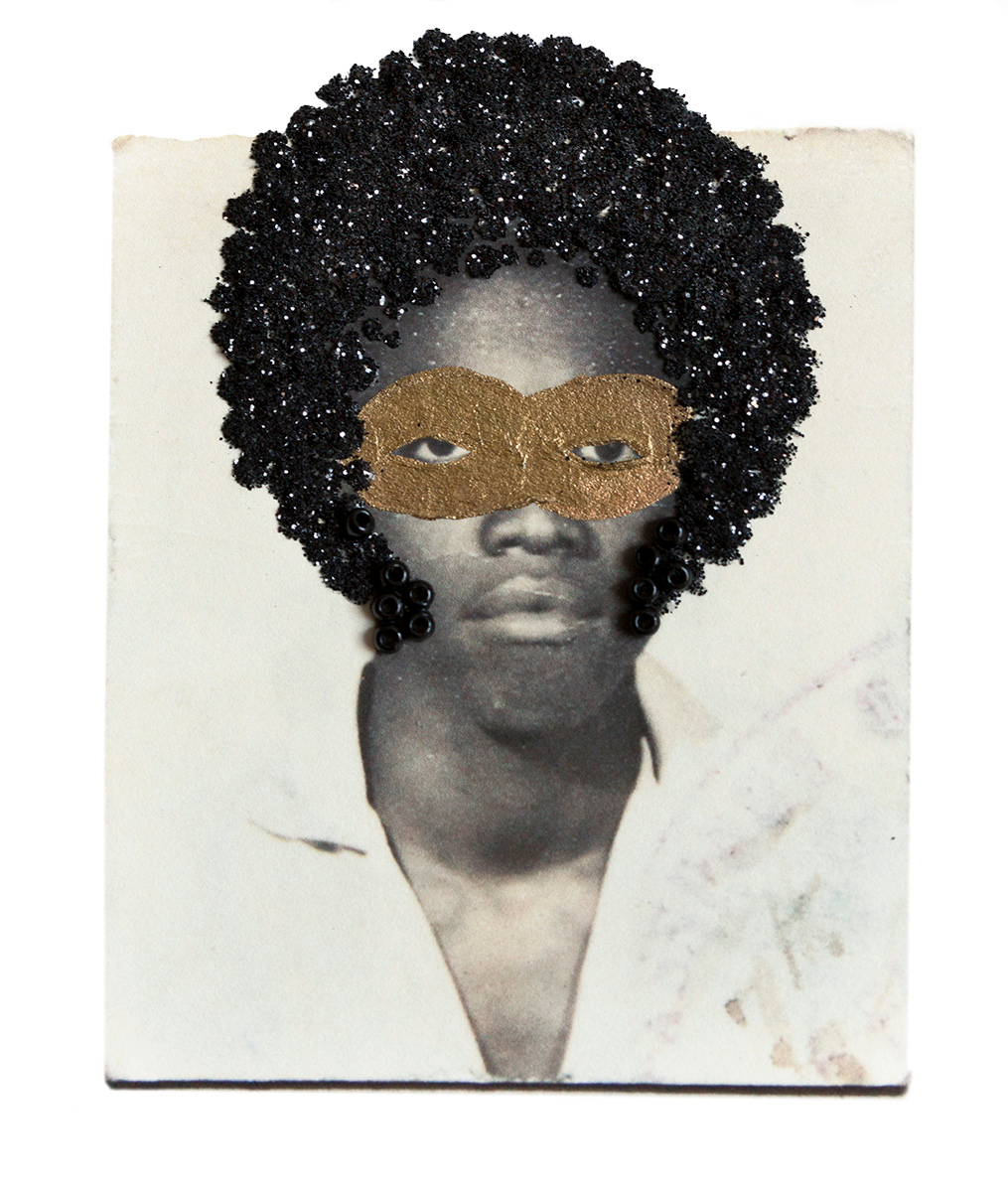

The basis for Keisha Scarville’s Passports series (2012 – ongoing) is a 1955 Guyanese passport photograph of her father, taken when he was a teenager. Growing up, she “would stare at it for long periods of time and look for clues about the young man frozen in the distant past.”[i] Scarville is fascinated by the fact that her father no longer thinks of himself as Guyanese but as American. What do we see when we look at passport photographs of ourselves or others? They are intimate objects that oscillate between the public and private spheres; a standardized form of portraiture that can abstract one’s identity and by doing so can turn one into a citizen, a foreigner, or an enemy. Informed by conversations with her father, Scarville tenderly adorns copies of his first passport photograph with paint, glitter, beads, collage, or erasure, creating seductive, otherworldly portraits. With each iteration, she attempts to make the inherently intangible, ever-morphing nature of identity tangible. Her gesture becomes a radical tool that unhinges her father’s image from its position within the international bureaucratic superstructure of the world, creating a constellation of narratives.

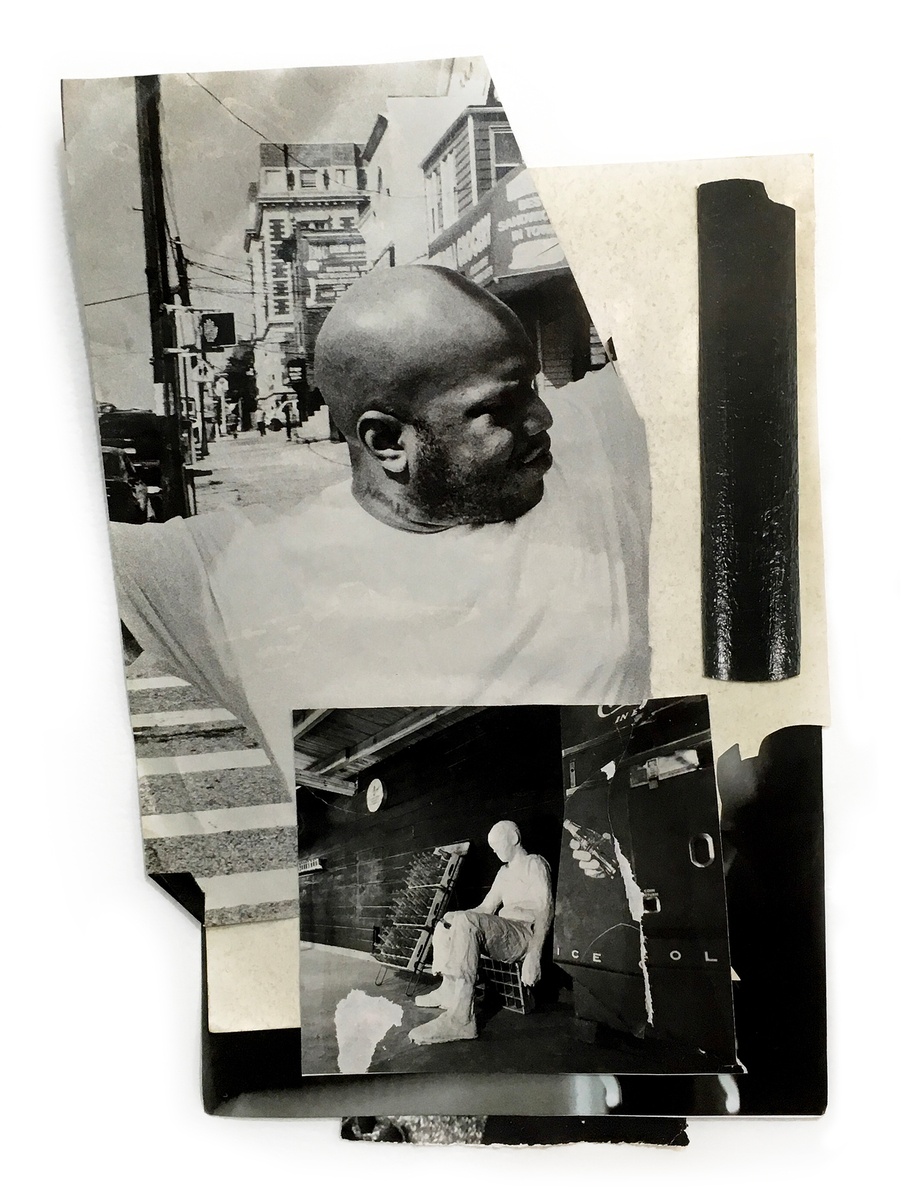

The collage work of Aaron Jones remixes consumer media to present notions of blackness via the carefully composed juxtaposition of seemingly unrelated content. The cut, ripped and torn sources of his work are print publications from the last 50 years: hip-hop magazines, lifestyle publications, National Geographic, and children’s books. In Jones’ only monochrome work, a profile portrait of a young man in an urban setting is positioned next to a pillar; below this pairing is a curious image of a papier maché figure that is placed next to a vending machine. The disparate elements seem to infer strength, solidity, and growth, perhaps asking: what does a glorified image of a black man look like? The remaining collages in the exhibition offer ambiguous, inventive figures. The legs and arms of the only person of colour in a recent issue of a Canadian fashion periodical serve as the appendages for fantastical forms that don marbled legs, crochet, crowns, and a mouth wide open in mid yell. Jones’ work inquires into the original contexts of his chosen imagery, offering modes of critical analysis, alternate associations and new stories.

Alexandra Bell analyzes language, narration, and information consumption. Through research she investigates how race, politics and culture are mediated. Her Counternarratives (2017) series consists of prints of New York Times articles and visualizes her careful redaction and interrogation of the newspaper’s headlines, text, and imagery; the works ultimately reveal the perpetuation of bias in journalism. Olympic Threat tackles the 2016 story of four white, male, American athletes who vandalized a gas station in Rio de Janeiro during the Olympics. The headline read: “Accused of Fabricating Robbery, Swimmers Fuel Tension in Brazil.” The Times paired the headline with an unrelated image of Usain Bolt winning gold, creating an exasperating adjacency. By replacing the image of Bolt with Ryan Lochte, Bell reveals the ways in which marginalized experiences are put forth. Bell’s bold red edits provide a literal (and gestural) undoing of racism, exposing how news media’s habitually coded language and imagery is used to ensure whiteness goes unnoticed.

Leslie Hewitt is a sculptor. Her Still Life series (2013) conjures unexpected connections and possibilities through the proximity of seemingly unrelated materials such as vernacular photographs, books, and wooden boards. Like Bell, although much more subtly, Hewitt pushes viewers to consider the connections between text and image, while foregrounding the materiality of objects. Featured in both Untitled (Candid) and Untitled (45º) is James Baldwin’s book The Fire Next Time (1963). The title of the exhibition is taken from the first essay in this book, a letter Baldwin wrote to his fifteen-year-old nephew. In it he describes the trajectory and conditions of race relations in America, calling on the young man to fight against and overcome racial oppression and white supremacy. Baldwin reminds him that he comes from “men who picked cotton and dammed rivers and built railroads, and, in the teeth of the most terrifying odds, achieved an unassailable and monumental dignity.”[ii] Hewitt’s inclusion of snapshots cast a familiar and nostalgic tone, but their adjacency to Baldwin’s book evokes modes of visual resistance—the production of imagery by and for black people—enacting what bell hooks describes as “a disruption of white control over black images.”[iii] The privately produced snapshots speak to the multiplicity of black life and experience, providing imagery that is counterhegemonic to visual representations created and put forth by mass media. They also provide an intimate complement to Baldwin’s collective and political sweep, collapsing the past and present, social and political, personal and public.

—

[i] Qiana Mestrich, “Photographer interview: Keisha Scarville.” http://dodgeburnphoto.com/2014/04/photographer-interview-keisha-scarville/ (accessed August 31, 2017).

[ii] James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time (New York: The Dial Press, 1963), 10.

[iii] bell hooks, “In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life,” in Art On My Mind (The New Press: New York, 1995), 59.

—

Upcoming programing

Saturday October 21, 2pm

Join Heather Rigg for an informal gallery walkthrough.

Saturday November 18, 1-3pm

Gallery Reading Group.

Attendants will discuss a selection of short essays that informed the exhibition.

—

Curated by Heather Rigg

Aaron Jones is an artist, curator, entrepreneur known for his work with collage. Working with lens-based mediums, he refers to himself as an image-builder, weaving together diverse materials from books, magazines, newspapers, and personal photos to forge captivating characters and alternate realities. These objects and images to explore the inherent possibilities in world-building and abstraction. Jones seeks to expand canonical Blackness, employing found images, and other tools to build characters and spaces that reflect upon the nuances of his own upbringing and current life, as a way of finding peace. Jones is represented by Zalucky Contemporary, Toronto.