Brendan George Ko The Forest is Wired for Wisdom

Toronto-based artist Brendan George Ko is a visual storyteller, using photography, video, and poetry to depict the natural world. Presented on billboards in 10 cities across Canada, The Forest is Wired for Wisdom comprises a series of luminous, almost incandescent images of flora nestled deep under the forest canopy, paired with poignant excerpts of Ko’s own poems. Together they offer passersby moments of contemplation and awe at nature’s beauty, while pointing to the forest ecosystem’s fragile interconnectivity.

L’artiste torontois Brendan George Ko est un conteur visuel qui dépeint la nature à l’aide de la photographie, de la vidéo et de la poésie. Présentée sur des panneaux d’affichage dans 10 villes du Canada, The Forest is Wired for Wisdom comprend une série d’images lumineuses, presque incandescentes, de la flore nichée au plus profond du couvert forestier, chacune étant associée à un extrait poignant des poèmes de Ko lui-même. L’ensemble offre aux passants des moments de contemplation et d’émerveillement devant la beauté de la nature, tout en soulignant la fragile interconnexion de l’écosystème forestier.

Ko’s billboard project is inspired by the work he produced for The New York Times in Nelson, BC, where he explored the forest understory with Canadian ecologist Suzanne Simard. Coming from a long line of loggers, Simard is now famous for her research on plant communication, specifically, the study of how tree species share information through mycelium—vast underground fungal networks. Simard stresses the important role mature trees play within a forest, supporting younger generations that include the fragile seedlings pushing their way through the rich forest-floor detritus of fallen leaves and brush. Her theories were initially considered controversial by many in the scientific community because they contradicted the core concepts of Darwinian evolution, pointing to cooperation as an essential element for strength and survival, and not only competition. Today Simard collaborates with biologists, timber companies, and Indigenous groups across the country on the experiment she calls “The Mother Tree Project,” working to create and champion sustainable logging practices that keep the healthiest, most established trees standing, to support new growth.

The title of Ko’s project is borrowed from a line in Simard’s book Finding the Mother Tree (2021), where she states, “The scientific evidence is hard to ignore: the forest is wired for wisdom, sentience, and healing.” The images presented range from an imposing view of a towering, old-growth Douglas fir, to scenes showing golden oak and lady ferns layered in the dense understory, to lichen growing south of the Arctic circle. Pyxie Cup Lichen I (2019), in vibrant, electric pink and blue against dark soil, appears almost otherworldly and microscopic. Paired with it is a line from one of the artist’s poems that reads, “Given time it all returns to the same, one form to another, all energy.” As a way of illuminating the “essence” or “spirit” of the plants, Ko applies a psychedelic colour palette to his images, heightening their dazzling impact. Pyxie Cup appears to reference Simard’s own wonderstruck description of the textures and tones of the forest floor upon seeing the vivid yellow, white, and dusty pink netting of mycelium tangled with the root system of a small seedling.

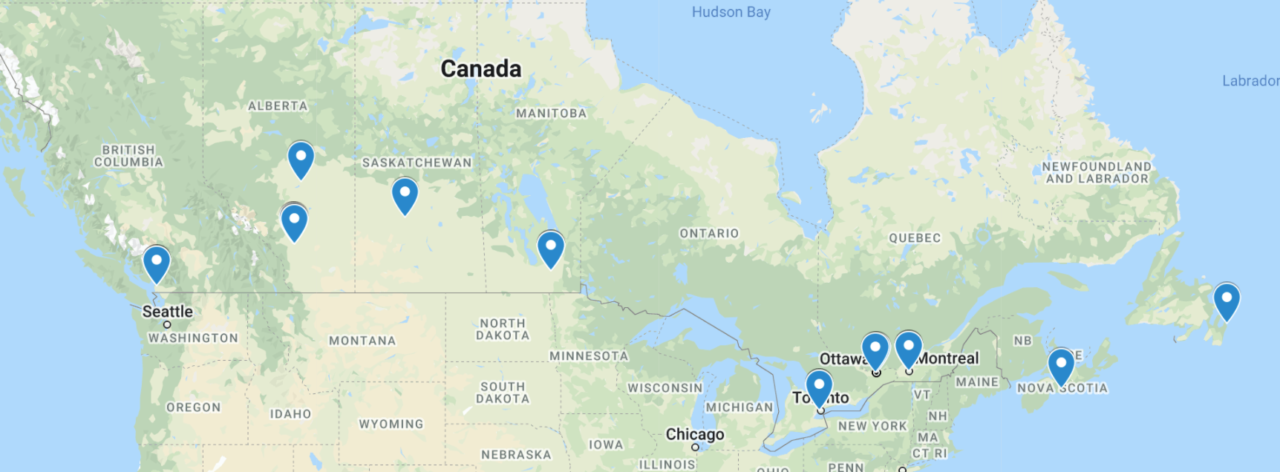

The forest is more than just a collection of trees—it’s a multigenerational, multi-layered ecosystem of great diversity, powering the essential carbon and nitrogen cycles vital to our planet. Far-reaching underground mycorrhizal networks span the whole continent, their symbiotic relationship between plant roots and fungi playing a key role in soil biology and plant nutrition. Shown on 25 large-scale billboards in a cross-country through line connecting Vancouver to Halifax, The Forest is Wired for Wisdom is a poetically playful allegory of the hidden networks below our feet. Ko’s photographs look beyond the surface, endeavouring to depict the nuanced essence of a place, a plant, or a moment. His work is a reminder of the larger connections at play in the natural world, or, in his words, a reminder to “let the words grow distant as we get lost to that place without form.”

Curated by Tara Smith

Presented by CONTACT. Supported by PATTISON Outdoor Advertising. Part of ArtworxTO: Toronto's Year of Public Art 2021–2022

Brendan George Ko is a visual storyteller working in photography, video, installation, text, and sound. His work conveys a sense of experience through storytelling, and he describes the image as supplementary to the story it represents. In 2010, Ko received his BFA from the Ontario College of Art & Design University, where he majored in photography, and he went on to the Master of Visual Studies programme at the University of Toronto, where his practice focused on video and sound.