Esery Mondesir We Have Found Each Other

Toronto-based artist-filmmaker Esery Mondesir mines personal archives, institutional collections, music, and oral histories to chart and connect people and places to his homeland of Haiti and to its diaspora, drawing from his own experience of migration. The film footage, score, passport photographs, and text presented in this exhibition reflect the extended family he has found.

Mondesir describes the impulse that fuels his art practice as “a search for kinship.” We Have Found Each Other draws connections between Toronto, Havana, Montreal, Port-au-Prince, and the Oti region of Ghana as part of this search. In the following artist statement, Mondesir adopts a fragmentary, narrative approach to describing some of the people and places he encountered while developing this body of work.

Kinship

Akpafu-Todzi sits atop Mount Ɔgagɛ in the traditional Akpafu territory in the Oti region of Ghana. The 600 or so Mawu people who live here call the place home up high—akaa i kato in their native Siwu language. Titi, the village chief’s spokesperson, says that only five babies were born here last year. This, he remarks, is evidence of an unfolding demographic nightmare caused by the exodus of young people to bigger cities. As crucial as this problem might be for a community of farmers, it is a shared reality among many places in rural England, Northern Ontario, or Haiti’s Far West. Here’s another truism about smaller towns worldwide: everyone knows everyone. I am, therefore, not surprised that Ajo, Todzi’s assemblywoman, would want to check my identity when she finds me roaming the Ɔgagɛ forest on her way to her cacao farm but her question startles me. What is your father’s name? I freeze. Then smile nervously: I am actually seeking a father, auntie!

— Hey, Miah. I’m doing well. I visited a place called Todzi today. Extraordinary!

— Oh nice, dad. Send pix!

Silvia Garde tells me you are my son now, as if she wanted to consecrate our chosen kinship. Ten years ago, we started working on a short film together in Havana, Cuba. The very first day we meet, Silvia and her siblings Siverio, Estella, and Odilia throw me a party. We were homesick—as if they were not born in Santiago, as if home was not shifting for me. Their mother, Gimène, smiles elegantly in a black-and-white photograph placed on a small altar in their living room, her eloquent face graced by candlelight. Like many Haitian seasonal migrant workers who arrived in eastern Cuba in the early 1900s, she will never fulfill the dream of going back home. Instead, she made home these filthy barracks around the bateys where Haitians and other Caribbean migrants worked in slave-like conditions so folks in Miami, Chicago, and Toronto could have their cafe latte sweetened. In those days, no one wanted to be Haitian, Silverio remembers. To resist total erasure, Gimène taught her children her mother’s tongue, and trained them to dance Mayi, Ibo, Petro so they could find each other and others like me could find them.

— So listen, son. I need your help locating a box of photographs to send to the folks at the AGO. Can you help?

— Yeah, they’re in a brown box, right? I saw them the other day, looking for the insurance card. I saw your dad for the first time. Wow, these genes are strong, lol. Are those all our family members?

Katherine Dunham and the Garde sisters never met. Yet, the circular motion that gracefully throws their shoulders upward, backward, downward, and upward again betrays common roots. Dunham arrived in Haiti in 1936 with clear academic goals in mind but she is said to have found personal connections, treasures that were also hers to claim and embody.

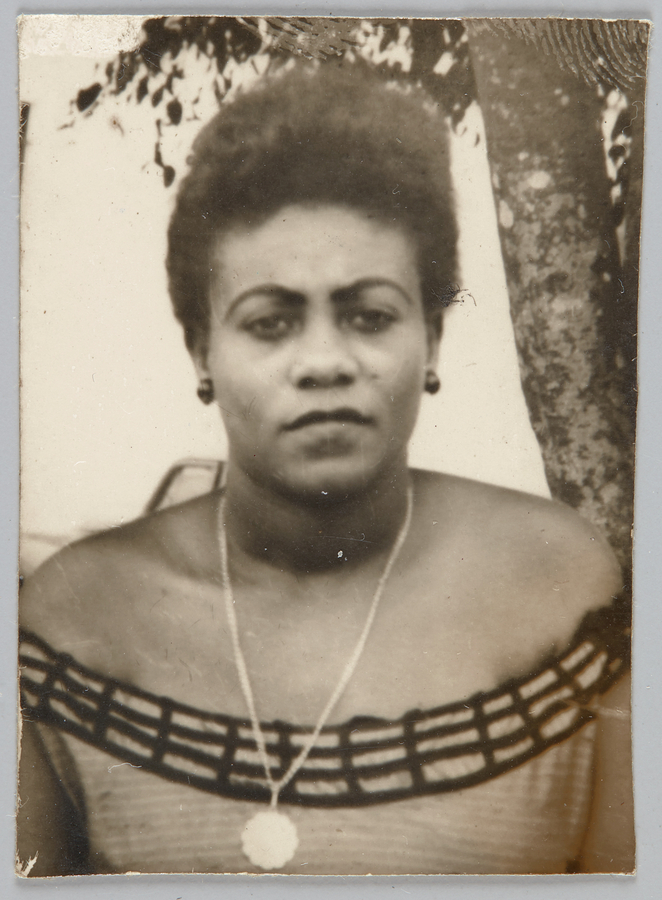

My elder and friend Frantz Voltaire finds everyone—living, dead, or otherwise. From his base in Montreal he is the poto mitan, the central pillar of the Haitian intellectual community in the diaspora through his work at CIDHCA, the Centre International de Documentation et d’Information haïtienne, caribéenne et afro-canadienne. He tells me that he often roams the streets of Port-au-Prince, Caracas, or Mexico City looking for a rare book, a news article, a piece of music, a trace. Sometimes, he doesn’t know or remember the particulars of his trouvailles, as in the case of these passport photographs of Haitian migrants, discarded on a street corner in Havana, Cuba. Were they political refugees, migrant labourers, traders, regular folks who moved to another place? What matters is that they were there. He found them, these treasures of kinship.

— I’m not sure your father’s picture is in there, son. Those are found photographs of Haitians in Cuba in the 1950s and 1960s.

— Wait, THIS is not your dad????

Curated by Sophie Hackett

Presented by the Art Gallery of Ontario

Esery Mondesir is a Haitian-born video artist and filmmaker. He was a high school teacher and a labour organizer before receiving an MFA in cinema production from York University (Toronto) in 2017. Mondesir’s work draws from personal and collective memory, official archives and vernacular records, and the everyday to generate a reading of our society from its margins. His films and video work have been exhibited in Canada and internationally. Mondesir currently lives in Toronto.