Tyler Mitchell Cultural Turns: CONTACT Gallery

Presented across three sites in Toronto—in an exhibition at CONTACT Gallery, and in outdoor installations at Metro Hall and on billboards positioned at the intersection of Dupont and Dovercourt—the work of American photographer Tyler Mitchell brings a bold vision to the city. His vibrant images richly portray the beauty, presence, and self-assurance of Black lives, referencing the rich history of Black photography while proposing new futures.

In the following essay, British curator and cultural historian Mark Sealy contextualizes Mitchell’s work within the frameworks of identity politics, human rights, the relationship of photography to social change, and the African diaspora.

Track 1

Tyler Mitchell’s images arrest the past. They resonate with history and call forth new ways of being. As photographs, they demand political and cultural turns that make it possible for us to see, imagine, and dream of everyday utopias and places where hypervigilance and the epidermal schemas of this world are no more. Across Mitchell’s work, pleasure reigns supreme. His images deconstruct oppressive conservative barriers: physical, psychological, political, or epistemological. This three-part project aims to function as a visual gift that encourages its audiences to sweep away all they may have inherited from photography’s grey and guarded old world. Here in the sharing of these images, we can collectively, as human subjects, feel the warmth of a new visual dawn; a heat that assists in melting away the destructive binary politics of “us” and “them” at work in this time. Within Mitchell’s world, Black bodies resonate with sensual warmth. Radically, then, across the arc of Mitchell’s praxis, the Souls of Black Folk can now rest as jazz-like free agents at ease in life.

Track 2

The curatorial gambit at work across these inquiries into Mitchell’s photography aims to tease out the visual formations that rest in the unconscious space of representational politics and the entangled histories of photography. We forget what we may have seen and heard in time, but this does not mean that words and images from the past are not at work in our present. The works curated for public presentation at Metro Hall and on the billboards at Dupont and Dovercourt have been chosen precisely because of their temporal and dialogic capacities across time. As a body of images, they are fused to and born within various cultural and historical ways of being. Mitchell’s photography is charged with a spell-like quality that arrests the violence of bygone Eurocentric, photographic time. These works speak to some of the more celebrated afro-photographic episodes in history. Tune in long enough, and these visual conversations begin to reveal themselves like aged but familiar old friends, recognizable even through the cracks of time.

Track 3

At Metro Hall, Mitchell’s photograph of two young women standing with a bicycle, Untitled (Southern Girls) (2021), radiates the presence of Malian photographer Seydou Keïta and the images he produced from his marvellous studio in Bamako. In the 1950s, the residents arrived there to celebrate their sense of self, not as objects before the camera but as subjects working with the camera. The radical act in the making of Mitchell’s photograph is that it spiritually and directly connects to a place of African affirmation, confidence, and beauty. This work is rooted in a decolonial praxis that guides the viewer toward the space of freedom, liberation, joy, and celebration. When harnessed by Mitchell, the energy emanating from within the African diasporic photographic cosmos is an unstoppable, regenerative force that fuels his desire to caress and embrace his subjects in light and colour.

American photographer James Van Der Zee’s star is also present; it shines with exuberant clarity through Mitchell’s photograph of a woman lounging in a bright red, open-topped car in Untitled (1932) (2021), also at Metro Hall. Her powerful gaze is only slightly muted by her white-rimmed sunglasses. This photograph works not only as a powerful image of a Black woman obviously in control of her destiny, but also pulls back into focus the iconic image that Van Der Zee took in Harlem in 1932 of a couple wearing matching racoon-skin fur coats, enjoying being framed with their top-of-the-range Cadillac V-16. As visual motifs, these images produce a defiant sense of Black being, one that sheds the degrading skins of categorization and classification so evident in photography’s past. Mitchell, Van Der Zee, Keïta, and the many Others working from within the African cosmos, generating images of Black people, are photographic time lords bonded through a form of overlapping, politically expedient, circular visual breathing.

Flip Side

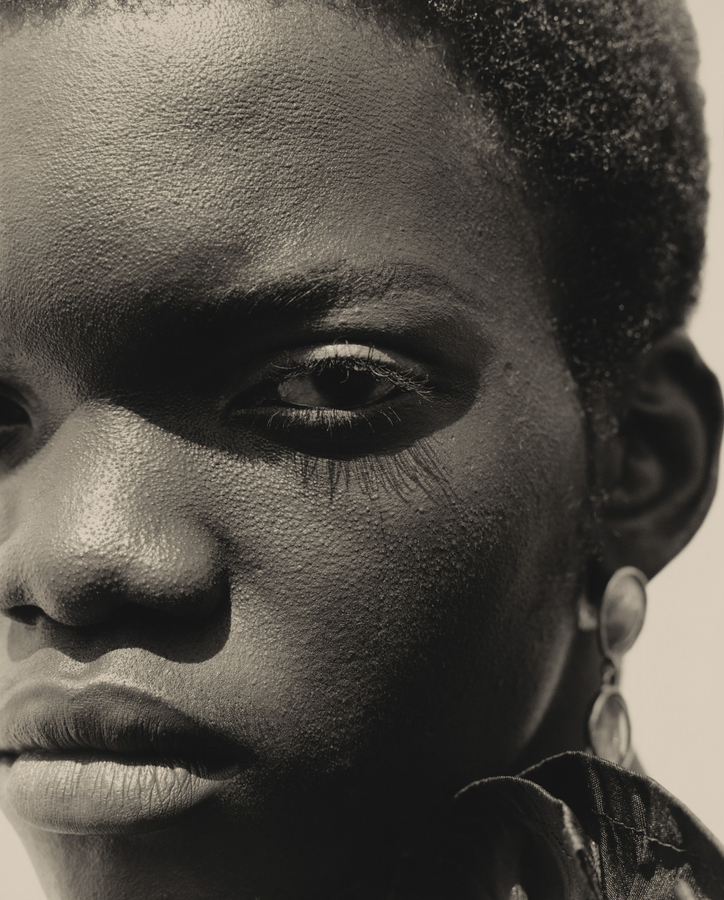

The puzzle of influence is never complete because the absorbent self is infinite. The jazz of Mitchell’s work is essential, as it keeps alive in the eye the beauty and vastness of all those voices that have contributed to the polychromatic nature of Black experiences. The photographs positioned on the billboards at the intersection of Dupont and Dovercourt are critical in the work they do in the public realm. One image brings you very close to the subject’s face, essentially framing her eye in sharp focus. As a photograph, Untitled (Eyelash) (2019) invites a narrative that promotes the intimacy of an encounter through the act of looking. Within this photographic moment, the subject’s gaze becomes an inescapable, all-seeing eye, suggesting that the subject is beyond the act of capture or framing. Here, the Black body is beyond the limits of being easily contained within the frames of this world. Mitchell has opened a portal through which we can see and be seen. Holding the vastness of Black subjectivity is outside the limits of our imagination.

On the flip side of this vast, billboarded, Other world, Mitchell brings into play a rare critical moment that offers the viewer the gift of understanding concerning the nature of masculinity. In Untitled (Sloane and Leo Embrace) (2019), two young Black men are shown at ease within their tactile affection for each other. The look on the young man’s face who returns our gaze suggests an expressive narrative that alludes to and echoes the coolness of Miles Davis’s hugely influential 1959 jazz classic, “So What.” Collectively, then, as photographs these works provide space to allow the eye to bathe in and be soothed by what can only be described audibly and visually as a Kind of Blue.

Notes

- The phrase “epidermal schemas” derives from Frantz Fanon’s Black Skins, White Masks, 1952.

- The Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches is a 1903 work of American literature by W. E. B. Du Bois.

- “So What” is from the album Kind of Blue by Miles Davis, 1959.

Curated by Mark Sealy, OBE, Director of Autograph London; Professor of Photography – Rights and Representation, University of the Arts London; and core member of Photography and the Archive Research Centre (PARC), London College of Communication

Presented by CONTACT. Supported by Cindy and Shon Barnett

Tyler Mitchell (b. 1995 Atlanta, GA; lives and works in Brooklyn, NY) is a photographer and filmmaker working across genres to explore and document a new aesthetic of Blackness. In 2018, he made history as the first Black photographer to shoot a cover of American Vogue for Beyoncé’s appearance in the September issue. A work from this series was acquired by The Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. Mitchell’s first solo exhibition, I Can Make You Feel Good (2019) at Foam Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam traveled to the International Center of Photography (NY)(2020), and he published a monograph with Prestel Random House in conjunction. In 2020 Mitchell was awarded the Gordon Parks Fellowship, culminating in an exhibition at the Gordon Parks Foundation Gallery, Pleasantville, NY (2021). Mitchell has lectured at a number of institutions including Harvard University, NYU, Paris Photo, and the ICP.