Ken Lum Scotiabank Photography Award

This exhibition, comprising signature series along with new works, celebrates the career of Canadian artist Ken Lum, winner of the 2023 Scotiabank Photography Award. Lum is internationally known for his conceptualist and often humorous approach, which draws on methods from cultural and social studies, semiology, psychoanalysis, and political philosophy. The artist’s impactful practice utilizes photography to investigate the relationship between language and representation in the public space. By doing so, Lum critically challenges the social hierarchies and dominant narratives related to identity, class, and gender that are always at play in capitalist and postcolonial societies.

The following text is an excerpt from Alex Alberro’s “A Better Lifeworld: History, Identity, and Difference in the Art of Ken Lum,” in Scotiabank Photography Award: Ken Lum (Göttingen: Steidl Verlag, 2024; pp159–174).

Ken Lum’s artistic practice explores how texts and images shape our understanding of identity, culture, and social structures. It draws on methods from cultural studies, social theory, semiology, psychoanalysis, and political philosophy. His artworks make plain that things gain meaning not because of what they contain in their essence, but in the shifting of relations of difference that they establish with other entities in a signifying field. Meaning, Lum’s art repeatedly insists, is fundamentally socio-historical and cultural. It cannot be fixed independently, outside of specific historical and cultural contexts and their array of signifying practices. Moreover, it is relational and positional, and in a constant process of redefinition. As contexts and practices change, the meanings of things do too.

Lum’s investigations of human subjectivity follow a similar logic. They start from a premise that identity is a series of temporary attachments to subject positions that are constructed for individuals and communities through discursive practices. As the artist revealed in an interview in 1998, he has long strived to create artworks that make spectators conscious of their in-between states: “[W]hat constitutes the subject…has been a recurrent theme in all my work. I insist that the subject itself is something in-between, … it’s a hybrid, always in the process of transformation.”1Ken Lum, in Lisa Gabrielle Mark, “Reflections on the Mirror: An Interview with Ken Lum,” Ken Lum: Photo-Mirrors (Banff: Walter Phillips Gallery, 1998), 11–12. The products of Lum’s artistic practice present meaning and subjectivity discursively as processes of positioning rather than fixed constructs, as things that happen over time, that are never stable, and that are subject to the play of social history and cultural difference.2By “discourse,” I refer to those figures or tropes that have real effects because of the “regimes of truth” they institute. On “regime of truth,” see Michel Foucault, “Truth and Power,” in Colin Gordon, ed. and trans., Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977 (New York, NY: Pantheon Books, 1980), 109–133.

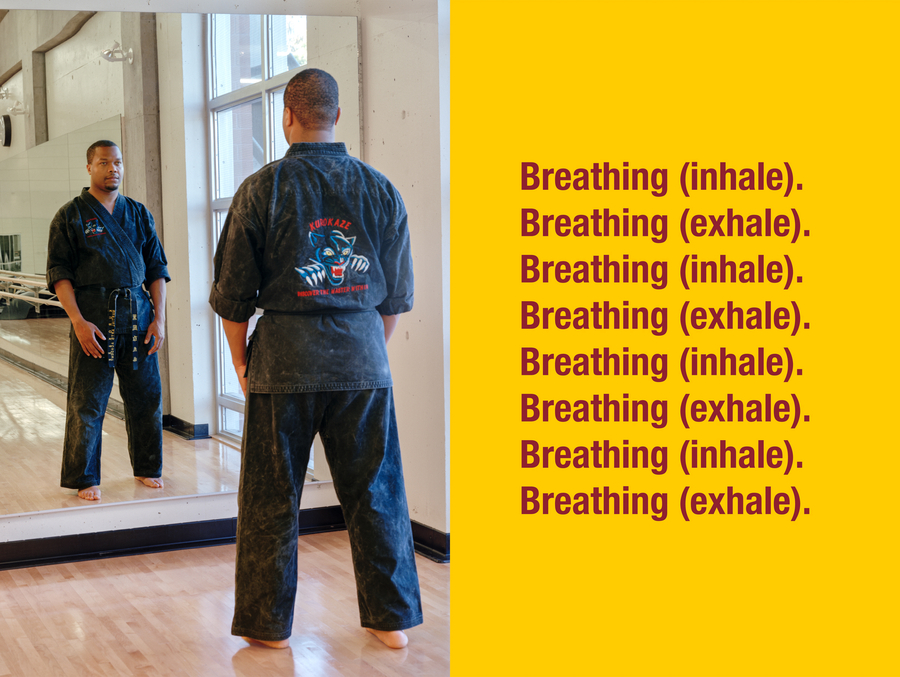

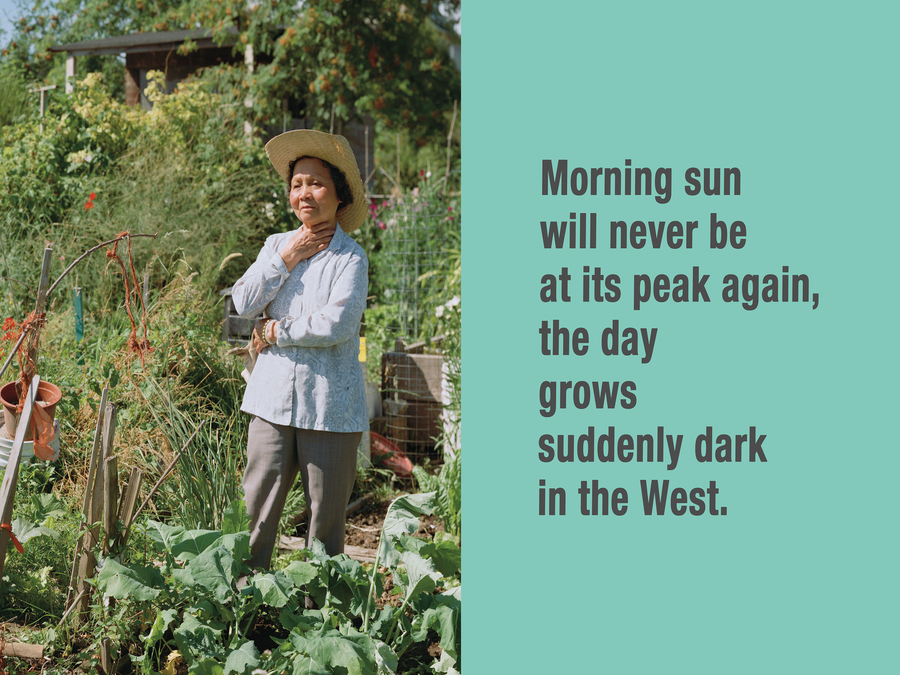

The photo-text montages Lum began to produce in the early 1980s explore the tension between images and words in the construction, dissemination, and subversion of signification. These artworks leverage the methods deployed by the advertising industry to attract attention and create meaning; they juxtapose photographs with laconic language in ways that evoke the graphic vocabulary, colour-coding patterns, and signifying techniques of adverts. Advertisements, however, have never been the vehicle of Lum’s work. Instead, the artist has long appropriated the aesthetic and semantic techniques of advertising to construct his art. Furthermore, unlike promotional notices with a conspicuous purpose, Lum’s artworks create tension between obvious interpretation and lack of clarity. Their exploration of the relationship between visual and written elements and the interplay between images and words grapples with the complex ways in which sign systems shape understandings. They challenge and disrupt stereotypes and dominant narratives, encourage critical engagement with issues of class, race, gender, and ethnicity, and highlight the need for diverse and inclusive representations.

Much of Lum’s artistic production addresses the relationship of text to image and vice-versa, prompting spectators to question whether the figures represented in the photographs correspond to the accompanying texts or whether the texts endow the figures with meaning.

[…]

[Lum’s work] raises questions about prejudicial generalizations and commonsensical notions of identity at the turn of the millennium. It unhinges and dislodges naturalized understandings of race, ethnicity, and nation, suggesting we comprehend these concepts as discursive constructs instead. Culture, the realm of shared languages, specific customs, traditions, and beliefs, constitutes the terrain for producing identity and identifications. It creates the signifying chains that place human subjects in social and historical relations. This process is one of the reasons social institutions strive for fixity. But culture is also the condition by which subjects can open up new possibilities for defining themselves and the collective identities, the “imagined communities” in historian Benedict Anderson’s sense, with which they identify.3Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London, UK: Verso, 2006). By interrupting the dominant signifying chains of race, gender, class, and ethnicity and leaving them in a state of ambivalence and strategic irresolution, Lum’s artworks set in motion a process capable of creating alternatives in which it becomes possible to rearticulate social reality more equitably and to imagine a more democratic lifeworld.

- 1Ken Lum, in Lisa Gabrielle Mark, “Reflections on the Mirror: An Interview with Ken Lum,” Ken Lum: Photo-Mirrors (Banff: Walter Phillips Gallery, 1998), 11–12.

- 2By “discourse,” I refer to those figures or tropes that have real effects because of the “regimes of truth” they institute. On “regime of truth,” see Michel Foucault, “Truth and Power,” in Colin Gordon, ed. and trans., Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977 (New York, NY: Pantheon Books, 1980), 109–133.

- 3Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London, UK: Verso, 2006).

Curated by Gaëlle Morel

Organized by The Image Centre, presented by Scotiabank, in partnership with CONTACT