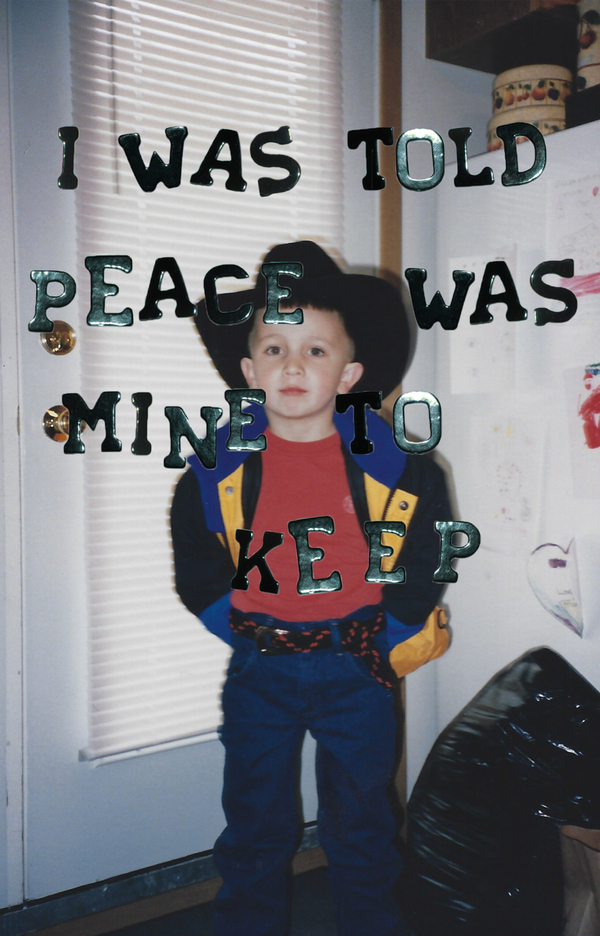

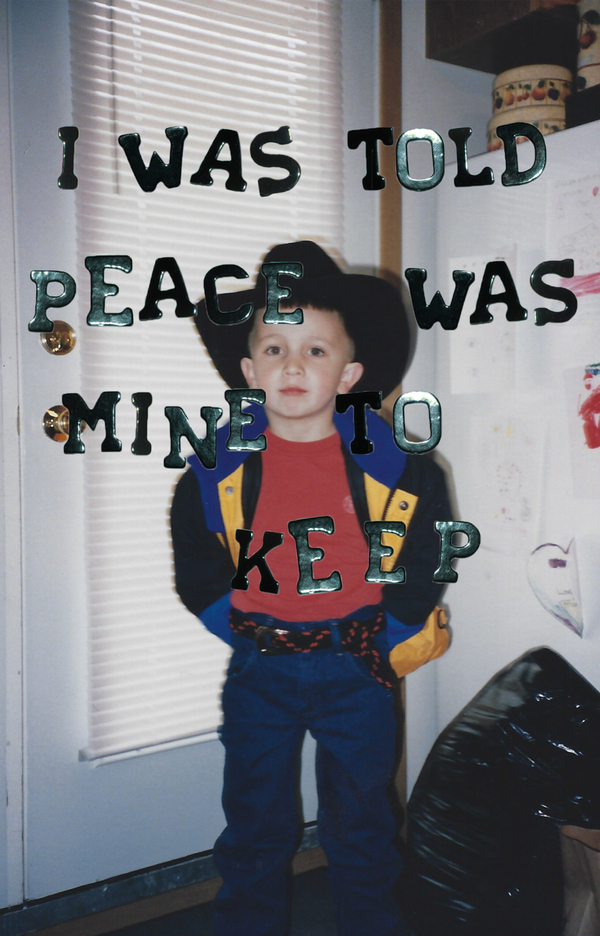

Jake Kimble Grow Up #1

Artist Jake Kimble, a Chipewyan (Dëne Sųłıné) from Treaty 8 Territory in...

Curated exhibitions and public art presented in partnership with institutions across the GTA

Artist Jake Kimble, a Chipewyan (Dëne Sųłıné) from Treaty 8 Territory in...

In their video, animation, and graphic works, Amsterdam-based artists Persijn Broersen and...

The work of Italian-Senegalese multimedia artist Maïmouna Guerresi invites viewers to look...

In this exhibition, Montreal-born, New York City-based artist Jean-François Bouchard documents a...

The New Generation Photography Award recognizes outstanding photographic work by three emerging...

Straddling the worlds of fashion photography and intimate portraiture, Jorian Charlton’s work...

Founded by Josef Adamu in Toronto in 2017, Sunday School is a...

Wolfgang Tillmans’s first museum survey in Canada foregrounds how the German artist...

Bringing together ten artists who highlight the vitality and range of contemporary...

This exhibition brings together Oreet Ashery, Common Accounts, Stine Deja, Charlie Engman,...

Emerging Toronto-based artists John Delante and Ananna Rafa navigate their respective cultural...

Brooklyn-based artist Genesis Báez grew up between the northeastern United States and...

Presented across three sites in Toronto—at CONTACT Gallery, on billboards, and in...

In tandem with his solo exhibition The Big Mess With Us Inside...

Waha (“oasis” in Arabic) is Moroccan photographer Seif Kousmate’s three-year–long research-based project...

Founded by Josef Adamu in Toronto in 2017, Sunday School is a...

Tkáron:to-based artist Erika DeFreitas engages with ritual and the divine feminine in...

Toronto-based photographer Scott McFarland presents Night Ship, a series of four large-scale...

Lobbies, doorways, and escalators populate Toronto artist Jessica Thalmann’s video essay, Latent...

Launched in conjunction with the 50th anniversary of The ArQuives—Canada’s only LGBTQ2+...

Presented across three sites in Toronto—at CONTACT Gallery, on billboards, and in...

Celebrating the legacy of American photographer George Platt Lynes, the male nudes,...

This outdoor component of the exhibition Materialized presents an image by newly-appointed...

Artist Jake Kimble, a Chipewyan (Dëne Sųłıné) from Treaty 8 Territory in...

Combining portrait photography with elements from adornment arts, textiles, sculpture, and customary...

Born in Harlem in 1941, June Clark emigrated in 1968 to Toronto,...

Working between the United Arab Emirates and New York, Lebanese-American artist Farah...

From its raw power to gentle ebbs and flows, the wave holds...

In Wish You Were Here, Toronto-based photographer Sarah Palmer documents the world...

Toggling between past, present, and future, Toronto-based artist Jawa El Khash’s project Nature’s...

In this exhibition, Toronto-based artist Colin Miner explores disturbance regimes and possible...

Too often Black art is understood solely through the lenses of identity,...

A member of the photo agency Ostkreuz, Berlin photographer Sibylle Fendt is...

Presented across three sites in Toronto—at CONTACT Gallery, on billboards, and in...

Korean-born, Vancouver-based artist Jin-me Yoon reflects critically upon the construction of national...

The two-channel video Braiding and Mending features South Korean-Danish artist Jane Jin...

This exhibition presents 19th and 20th century vernacular objects from the Lorne...

This project by Canadian artists Johanna Householder & Judith Price comprises seven...

This new body of work by multidisciplinary artist Maja Klaassens, born in...

Serapis is an Athens-based multidisciplinary collective that takes their inspiration from water—oceans...

Meryl McMaster (b. Ottawa, 1988) is a leading contemporary artistic voice, producing...

Berlin-based artist Aziz Hazara’s practice is deeply engaged with the geopolitics and enduring...

In the series featured in this exhibition, South African photographer Karabo Mooki...

Togolese-Belgian photographer Hélène Amouzou creates distinctive imagery through long exposures, generating photographic...

Vancouver-based artist Jayce Salloum presents an installation of photography, drawing, and sculptures...

This work by Finnish photojournalist Sami Kero is part of Mobile Sweat—an...

The world we live in is the global generic city we experience...

Known for his inspiring colour vistas of urban architecture and landscape, Canadian...

American-Canadian photographer Lynne Cohen (1944–2014) is known for her striking photographs of...

more-than-human features ten contemporary artists who explore human-natural relationships through technology, promoting...

The Inuit Art Foundation and Onsite Gallery present Up Front: Inuit Public Art...

This exhibition brings together a selection of photographic works by Newfoundland artist...

Based in the territory of Treaty 18, FASTWÜRMS’ witch queer #VOLCANO_LOV3R is...

Since 2019, Toronto-based artists Vid Ingelevics and Ryan Walker have photographically documented...

Presented as a billboard on The Power Plant’s south façade, these times,...

In tandem with the commissioned billboard project Just How We Found It,...

For the past twenty years, Winnipeg-based artist Sarah Anne Johnson has devised...

The recipient of the third annual Prefix Prize is Karen Zalamea, a...

Simon Shim-Sutcliffe’s The Machine Eclipsed by the Station presents a new installation...

This exhibition by Trinidad-born artist Rodell Warner features a series of animated...

Featuring works derived from the unique creative practices of Cassils, Suzanne Nacha,...

As acclaimed Spanish artist Lara Almarcegui's first solo exhibition in Canada, this...

Tackling Canada's colonialist history, this exhibition marks the 100th anniversary of the...

Fuelled by an interest in the relationship between Mexico and Canada, the...

Using her experiences within the medical system as a point of departure,...