Jane Tingley with with Faadhi Fauzi and Ilze (Kavi) Briede, (ex)tending towards, 2023, (3D visualization, cork, electronics, earth, point cloud). Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Jane Tingley

Jane Tingley with with Faadhi Fauzi and Ilze (Kavi) Briede, (ex)tending towards, 2023, (3D visualization, cork, electronics, earth, point cloud). Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Jane Tingley

more-than-human features ten contemporary artists who explore human-natural relationships through technology, promoting new ways of understanding the natural world. Each interactive artwork uses digital media to challenge, excite, and shift our collective understanding of the more-than-human mind. Inspired by an ethics of inclusion that acknowledges the rights of nature, the exhibition questions what it means to be alive and have agency.

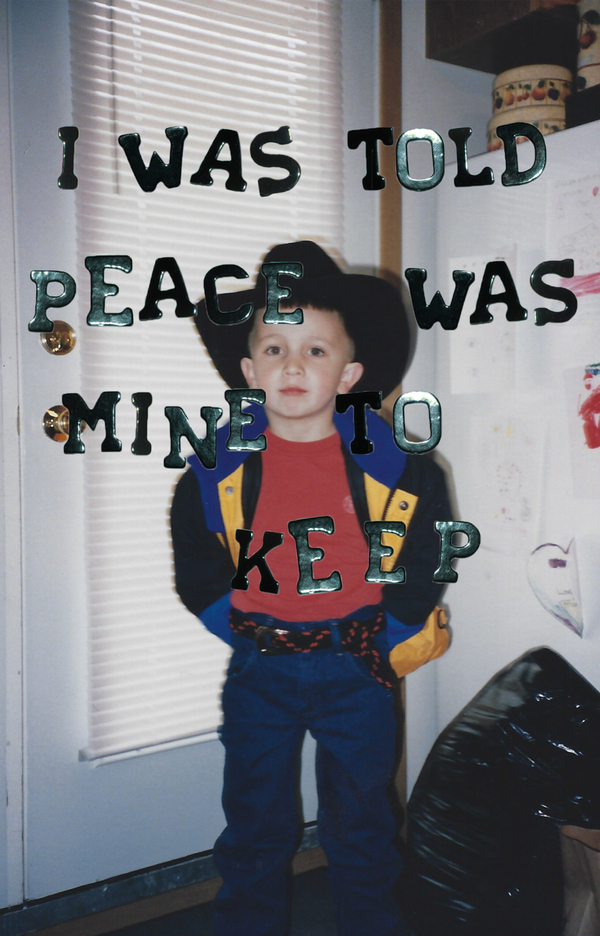

Mary Bunch and Dolleen Tisawii’ashii Manning, Emerging from the Water, 2022, (virtual reality). Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Dolleen Tisawii’ashii Manning

Mary Bunch and Dolleen Tisawii’ashii Manning, Emerging from the Water, 2022, (virtual reality). Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Dolleen Tisawii’ashii Manning

The concept of animacy hierarchy, introduced in Mel Y. Chen’s book Animacies (2012), describes a worldview that divides those entities that seem to be alive from those that are deemed to not be living: birds, trees, rocks. This hierarchical organization effectively privileges human life over all other lifeforms—including vertebrate and invertebrate, insect, and vegetal. An underlying source of this animacy hierarchy view, as argued by ecofeminist and philosopher Val Plumwood, is the strongly dualistic structure of Western thought: man/woman, mind/body, individual/surroundings, culture/nature. This bifurcating mindset includes the human-nature dualism, a conceptual schism that has rendered those that do not look like us, nor speak like us “as an insignificant Other, a homogenized, voiceless, blank slate of existence.”1 It is a “perception of nature” that has given rise to economic and societal structures that see the natural environment as nothing more than a resource for exploitation, and certainly not part of our sphere of moral consideration. In short, it is a way of thinking that underwrites and justifies the “domination of the Earth.”2

It is important to recognize that many cultures, including Indigenous Peoples worldwide, have neither these conceptual schemas nor a divisive worldview, but rather see nature as possessing more-than-human intelligence consider plants and trees as individuals, and understand that plant, animal, and human realms interpenetrate, sharing both heritage and substance. There are many commonalities between recent Western scientific discoveries and these ancient, long-standing Indigenous knowledges and epistemologies. Colonialism and industrial capitalism have all but destroyed a way of life and a perspective that sees the natural world as vibrant, alive, and filled with non-human lifeforms—both visible and non, both alive and not.

Lindsey french, Phytovision, 2018–19. Courtesy of the artist

Lindsey french, Phytovision, 2018–19. Courtesy of the artist

Western science is only now confirming what has been understood by other peoples for centuries if not millennia: that trees are living beings, have complex sensory systems, interact with their surroundings, make decisions and change their behaviours, are highly social, have families, can learn, and even communicate and care for each other. These discoveries challenge the concept of plant blindness.3 Recent events like the COVID-19 pandemic have demonstrated without a doubt that the body is not separate from its environment. To achieve a more sustainable life on the planet, we need to rethink, reconceptualize, and resituate everything “human” in relation to the environment accordingly. To recognize how deeply interconnected we are within a larger, more complex system, where all parts of that system are equally important and form a dynamic whole, is ultimately an ethical matter.

The exhibition more-than-human brings together artists, Indigenous leaders, scholars, technologists and scientists to build connections across diverse knowledge fields, and grew out of a research project that I have been working on since 2018 entitled Foresta-Inclusive. The title of this work came from the book Forests: The Shadow of Civilization (1992)by Robert Pogue Harrison, where he examines the historic relations between Western civilization and forests, and identifies “that the word itself, foresta, means literally ‘outside.’” Human civilization is outside of the forest, and the forest is outside of the human experience. Foresta-Inclusive emerged from a desire to reintegrate the forest and the human and to find ways through art making to inspire a deeper sense of empathy and responsibility for the forest. The related, but wider overarching goal for this research project is to completely unsettle the mental habit of assuming that humans are superior to everything else on the planet. In totality the exhibition will illustrate inclusively, somatically and experientially that we are participants in a more-than-linguistic dialogue with many parts of a larger more complex ecosystem—a system that is comprised of singular voices and stories shared through scent, vibration, colour, and other phenomena beyond human sensory capability.

Ursula Biemann, Forest Mind, 2021, (sync 2-channel video installation, 31 mins). Courtesy of the artist

Ursula Biemann, Forest Mind, 2021, (sync 2-channel video installation, 31 mins). Courtesy of the artist

Art has a tremendous capacity for telling stories about the experiences of others, drawing the viewer into these stories and encouraging the development of empathy. Art at the intersection of science and technology is uniquely positioned to tell more-than-human stories as the artists repurpose and reorient the scientific and technological tools of “visualizing” complex, invisible phenomena operating everywhere yet beyond human sensory perception. Once we can both sense the world from a humanist, plural perspective and think of the world from multiple (but not dualistic, not hierarchical) perspectives, it becomes possible to have productive discussions that can lead to real inclusive change. It is essential that we shift our collective understanding about the sophistication and vitality of non-human, even what we might consider “non-living,” agents to develop an ethics of inclusion that would enable a radical transformation of our perceptual capacities, our conceptual schemes, and our laws, such as the legal “rights” of nature. As scholar T. J. Demos suggests in his book Decolonizing Nature: Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology (2016), “art holds the promise of initiating exactly these kinds of creative perceptional and philosophical shifts, offering new ways of comprehending ourselves and our relation to the world differently.”4

The exhibition more-than-human is a group show of media artworks at the intersection of these four promising nodes: art, science, Indigenous worldviews, and technology. The works in the show speculatively and poetically use multimodal storytelling as a vehicle for interpreting, mattering, and embodying more-than-human ecologies, with the goal of critically and emotionally engaging with the important work of de-centring the human, even while the viewer is that human. Many of the works use technological and scientific tools as entry points for witnessing and interacting with these more-than-human worlds, as they help visualize phenomena beyond human sensory perception while nevertheless situating us within them. Together the works in the show offer embodied and felt perspectives that interweave scientific and Indigenous perspectives, opening the wild possibility of a discovery being a remembering.

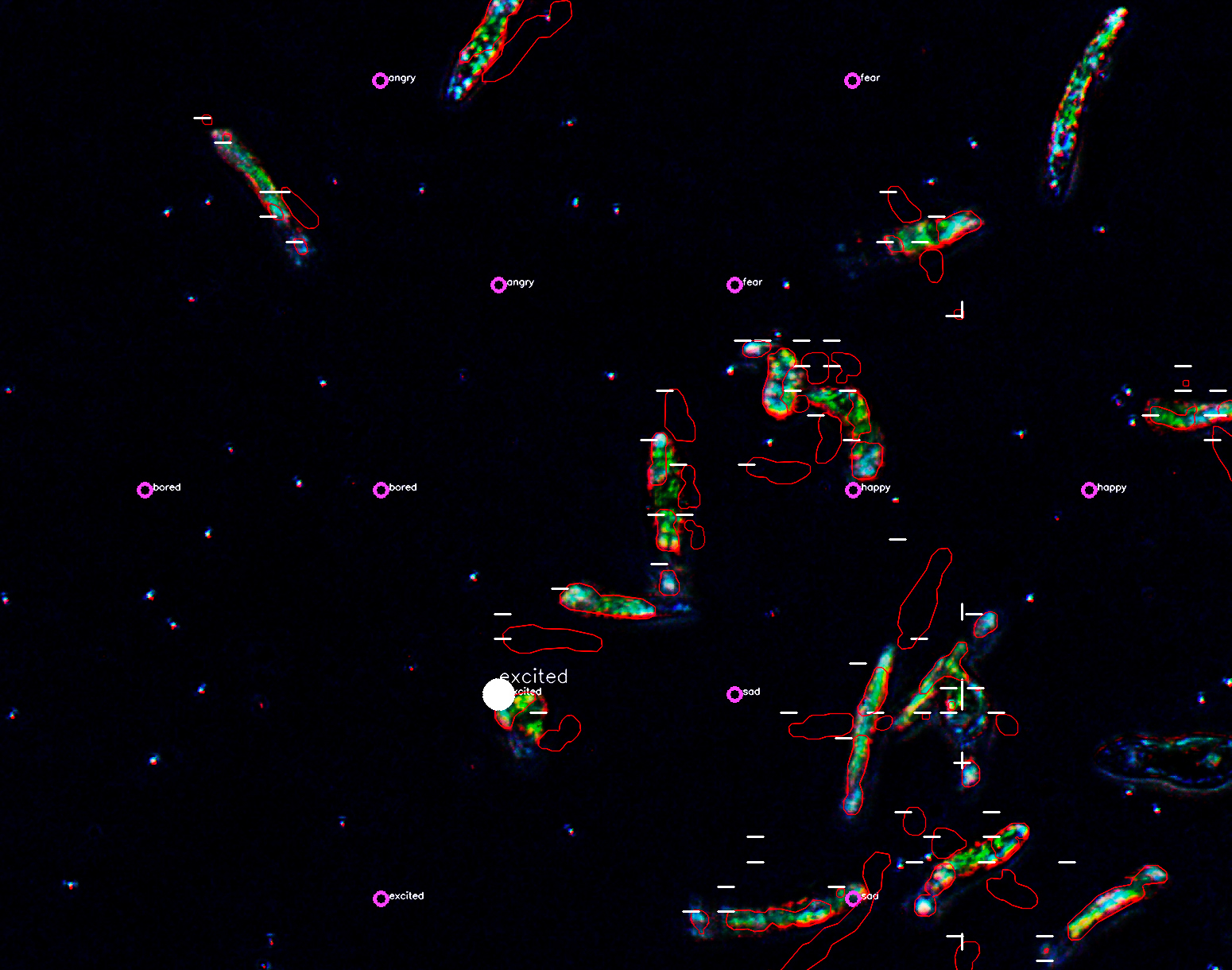

Suzanne Morrissette, one and the same, 2016, (interactive installation with Kinect and MAX). Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid

Suzanne Morrissette, one and the same, 2016, (interactive installation with Kinect and MAX). Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid

Human ontologies and stories are not the only way to understand and thus structure the living world. Many stories are unfolding in every direction at once, with just as many narratives and perspectives.5 The storytelling of microbes, protozoa, mycelia, bees, and plants are not necessarily about the world we humans are building. The humbling act of recognizing that we are not the only ones, not at the centre and not even the subject of others’ conversations can support our rethinking of our “truths” about ourselves, our place in the world, and the nature of our relationship to multiplicity and difference. Beyond helping us perceive the complexity of the world around us by visualizing and studying phenomenon that exist beyond limited human sensory perceptions, this recognition also shifts our imagining of the impact we have on the planet—on life.

The artworks in this exhibition ask: What does it mean to “be alive” and to “have agency”? How does re-training ourselves to slow down and listen to voices that have been marginalized or forgotten for millennia actually work? What could it mean to be “in dialogue” with something that does not share the same language or spatio-temporal reality? Once we authentically acknowledge the aliveness of something, what are the concrete ethical implications of that recognition that spill beyond the experience of an art exhibition in which that acknowledgement happened?

Grace Grothaus, Dawning, 2022, (envirographic video installation). Courtesy of the artist

Grace Grothaus, Dawning, 2022, (envirographic video installation). Courtesy of the artist

Dawning identifies the circadian rhythm as a chorus that all creatures on the planet participate in. Grothaus visualizes the canopy of the forest, affected in real time by live forest data, inviting the human to join into a rhythmic global song that connects all living things.

Emerging from the Water images an immersive field of underwater relations—a microscopic universe that vibrates with other-than-human potencies. This work is based on Manning’s Anishinaabe philosophy of Mnidoo-Worlding and Bunch’s media arts worldmaking research.

(ex)tending towards, by Tingley with Fauzi and Briede, uses live sensor data collected from the rare Charitable Reserve in Cambridge Ontario to drive a 3D visualization, a scent sculpture, and other phenomenon to create experiential installations that propose a new temporal experience when engaging with the forest.

Forest Mind is a film inspired by several years Biemann spent collaborating with the Indigenous Inga community in Colombia. This film explores the intelligence of nature and the intelligence in nature, viewed from both a Western science and shamanic perspective. The film looks at DNA technology—a Western approach to understanding what the Inga people understand to be a vital force that permeates all that exists.

One and the Same investigates the ways worldviews are reflected in our ideas and relationships with landscape. Morrissette’s work sets up a one-to-one relation between viewer and landscape that enables the viewer to engage and consider their own impact on the environment.

Phytovision asks the viewer to become plant, by offering an environment that filters the world through the sensory realities of vegetal life. In french’s work, the viewer can see through the same colour spectrum, hear through vibration, and smell the world of vegetal life.

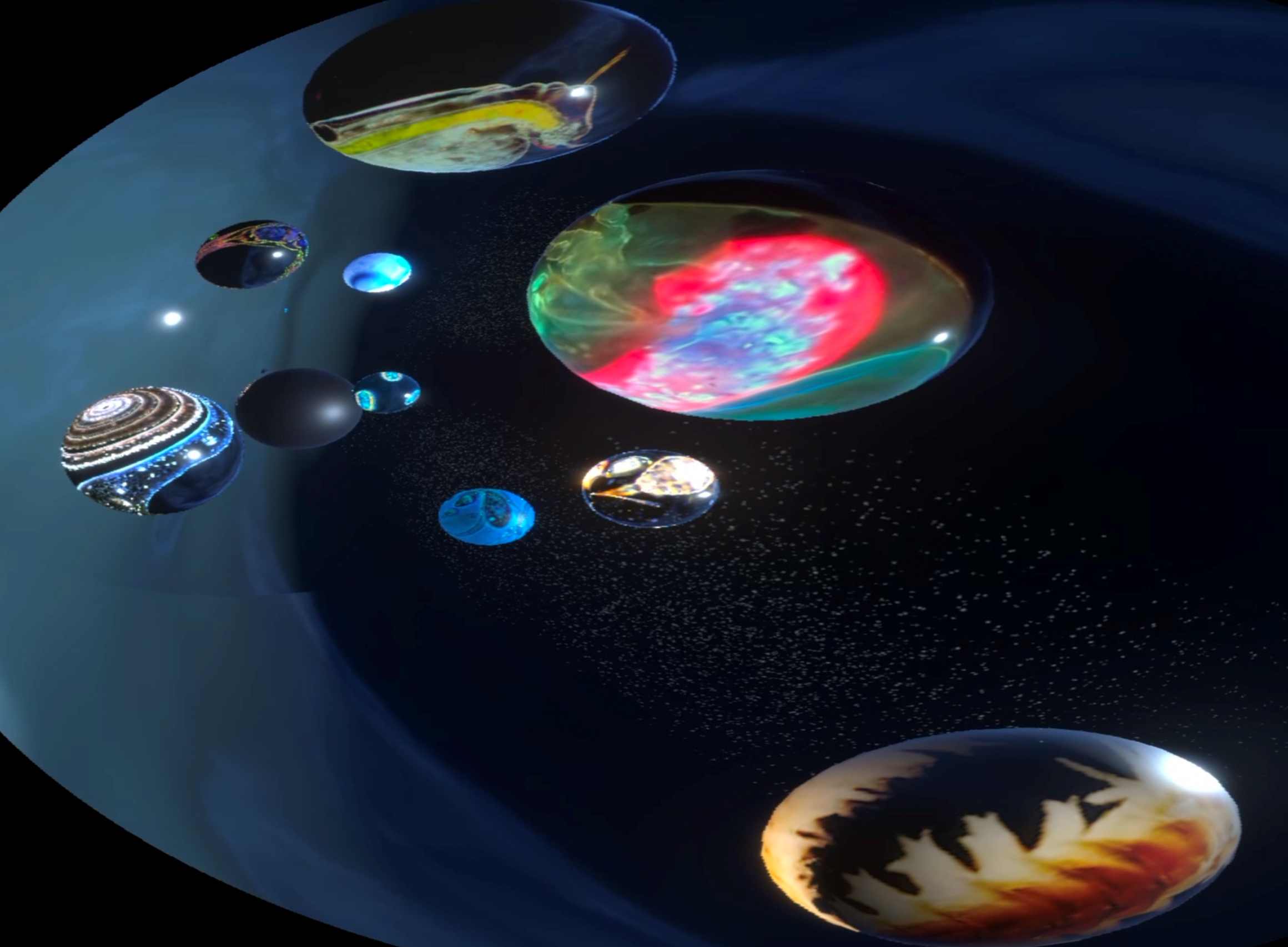

Joel Ong, Untitled Interspecies Umwelten, 2021, (photo still of live microscopic feed). Courtesy of the artist

Joel Ong, Untitled Interspecies Umwelten, 2021, (photo still of live microscopic feed). Courtesy of the artist

Untitled Interspecies Umwelten is an artwork that challenges the idea that language is a communicative structure that is human determined. Using a computer system, Ong speculates about ways in which interspecies communication structures might look.

Atmospheric Forest – Smite & Smits worked with scientists researching the Pfynwald Alpine coniferous forest in Switzerland, a forest suffering from drought due to climate change. The work visualizes the complex and hard to understand relations between the forest, climate change, and atmosphere.

Combined, the works in the show weave a story that tells a tale of symbiosis, intersections, and more- than-human relationality. The works combine scientific, philosophical, and Indigenous perspectives to create an experiential tapestry that asks the viewer to reconsider, reorient, and rethink relationships with the more-than-human. Asking again: Once we are shifted, once we authentically acknowledge the aliveness of the more-than-human, what are the concrete ethical implications of that recognition that spill beyond the experience of an art exhibition in which that acknowledgement happened? Has the concept of accountability not also shifted?

Rasa Smite & Raitis Smits, Atmospheric Forest, 2020, (immersive VR installation). Courtesy of the artists

Rasa Smite & Raitis Smits, Atmospheric Forest, 2020, (immersive VR installation). Courtesy of the artists

Curated by Jane Tingley

Presented by Onsite Gallery in partnership with CONTACT

FOOTNOTES

1. Matthew Hall, Plants as Persons: A Philosophical Botany (State University of New York Press, 2011).

2. Hall, Plants as Persons.

3. Plant blindness refers to the phenomenon of humans overlooking plants as living beings. See James H. Wandersee and Elisabeth E. Schussler, “Preventing Plant Blindness,” The American Biology Teacher 61(2) (1999): 82–86.

4. T. J. Demos, Decolonizing Nature: Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology (Sternberg Press, 2016), 19.

5. Karen Houle, “Symmetry and Asymmetry in Conceptual and Morphological Formations,” in From Deleuze and Guattari to Posthumanism: Philosophies of Immanence, eds. Christine Daigle and Terrance H. McDonald (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2022).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Chen, Mel Y. Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect. Duke University Press, 2012. Demos, T. J.

Decolonizing Nature: Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology. Sternberg Press, 2016.

Hall, Matthew. Plants as Persons: A Philosophical Botany. State University of New York Press, 2011.

Harrison, Robert Pogue. Forests: The Shadow of Civilization. University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Houle, Karen. “Symmetry and Asymmetry in Conceptual and Morphological Formations.” In From Deleuze and Guattari to Posthumanism: Philosophies of Immanence, edited by Christine Daigle and Terrance H. McDonald. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2022.

Plumwood, Val. Environmental Culture: The Ecological Crisis of Reason (Environmental Philosophies) 1st ed. Routledge, 2001.

Plumwood, Val. Feminism and the Mastery of Nature (Opening Out: Feminism for Today). Routledge, 1994.

Wandersee, James H., and Elisabeth E. Schussler. “Preventing Plant Blindness.” The American Biology Teacher 61(2) (1999): 82–86.