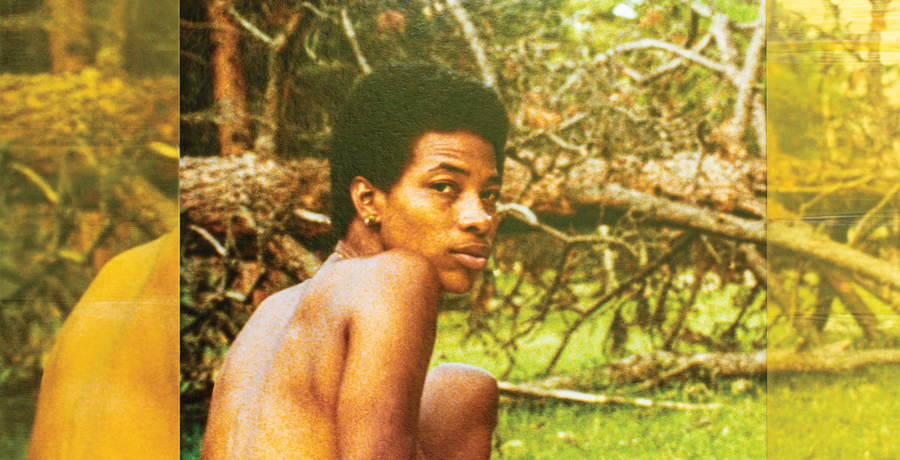

Alanna Fields, COME TO MY GARDEN, 2021. Courtesy of the artist

Alanna Fields, COME TO MY GARDEN, 2021. Courtesy of the artistAlanna Fields’s work is the result of a persistent search that attends an unwavering longing. Over the better part of a decade, the U.S. artist has dedicated tireless time and resources on a journey to discover and recover traces of Black queer life from the past. Her interest reaches backward to a time before she was born—long before our contemporary moment, in which queer identities and iconography are increasingly detached from their origins, commodified, and casually tried on at will. Rather, Fields concentrates her search on a bygone time whose interpretation is often skewed by official historical accounts. Her attention is attuned to a realm beyond the more ubiquitous historical vestiges, marked by fear, vitriol, tragedy, political strife, or battles for equal rights and their attendant violence.

Counter to common perceptions and prevalent histories, Black queer life has existed outside of sensational headlines, and in spite of social marginalization; this fact drives Fields in her pursuit to foreground such examples. This quest has taken her as far back as the mid-to-late 19th and early 20th centuries, the days of tintypes and cabinet cards, with her sights set on photographic glimpses of the quotidian, quiet, and intimate domestic interstices. Through these archival findings, she directs our attention to seemingly innocuous details—mannerisms, gestures, posture—the ways the subjects present themselves in relation to the camera. Their sartorial choices, makeup, jewelry, or the garlanded interiors in which they are photographed are all cues for Fields. They are surfaces to project onto, a means by which Fields bears witness to and finds affinity with the distant lives behind these archival residues.

Collectively titled Unveiling, the three images selected for this public presentation on billboards in Tkaronto/Toronto each narrow our view toward a singular figure, anonymous, staring directly into the camera and out at us in the present. The direction of their eyes is the communicative centre of the image, endowing them with a level of agency in how they are perceived. We don’t get to cast our gaze upon them casually; rather, they repel it back at us.

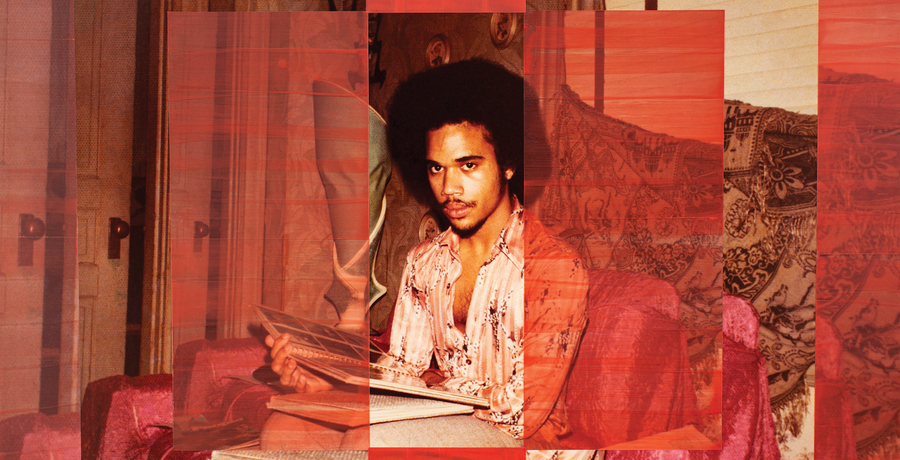

Alanna Fields, CLOSE YOUR EYES AND REMEMBER, 2021. Courtesy of the artist

Alanna Fields, CLOSE YOUR EYES AND REMEMBER, 2021. Courtesy of the artistThe images all share the visual cues of vernacular analogue photographs from the 1960s and ’70s—the hues, haircuts, fabric patterns, to name a few. Come To My Garden (2021) features a figure casting a sidelong glance, as they sit shirtless in a sylvan landscape. This glance, though attentive, is unbothered and self-assured. A second work, Close Your Eyes and Remember It (2021), is photographed indoors in what looks like a living room. The figure at its centre has an expressionless, uplifted stare, caught in an in-between moment. The third piece is the most closely cropped, focusing on a lone figure’s transfixing glare. Among the three, Distant Lover (2020) best expresses the critical refusal that undergirds this set of works. The figure’s direct eye contact is made more stark with his countenance awash in a flash of light. It approximates bell hooks’s description of the “oppositional gaze,” a political and cultural defiance embodied in the very act of looking critically and looking back.

As the series’ title suggests, subtlety isn’t of interest here. Because why should Black queer presences in history remain marginal or in any way subtle? The veiling implied in the title is one of subjugation. Unveiling, in turn, refuses to be a mere footnote in history, or to remain outside of public consciousness. To unveil, here, is an act of refusal. It is the refusal of a life of covertness and of the labour of palatability—the result of pervasive social conditioning that demonizes queerness, especially in the distant and not-so-distant pasts from which Fields’s work stems. To unveil is also to refuse to be imprisoned by one’s own identity—a recessive self-disciplining enacted as an outcome of the world we exist in. To unveil, here, is to refuse respectability politics as not only a Black individual but also as a queer one. The fact of the images’ scale and presentation, wide open in public space, only amplifies this series’ intimation of the desire for an unfettered life, lived without fear and in the superlative.

Alanna Fields, DISTANT LOVER, 2021. Courtesy of the artist

Alanna Fields, DISTANT LOVER, 2021. Courtesy of the artistFields’s collected archival fragments are often sourced from estate sales, eBay, or other online auction marketplaces. She never merely re-presents her findings as they are; instead, the artist saturates the images with her own visual interpretation. In so doing, she breathes new life into them, laying a personal, tactile patina of history atop. The resulting work is a mixed-media object that typically includes encaustic paint and mica flakes on panel or canvas. The artist duplicates and offsets the original image in repeated sections, creating something akin to a kaleidoscopic portal into the space-time from which the images echo out. These constructed, hand-applied embellishments are evident on the surfaces of the pieces included in Unveiling.

Fields has described her inexhaustible archival work as a gift to her younger self, who grew up without seeing nuanced images of Black queer individuals. To extend that remark, it can be said that the searching for, gathering, and preservation of discarded objects is also, in many ways, a searching for, gathering, and preservation of one’s own selfhood.

Presented by CONTACT. Supported by Pattison Outdoor Advertising

Curated by Luther Konadu