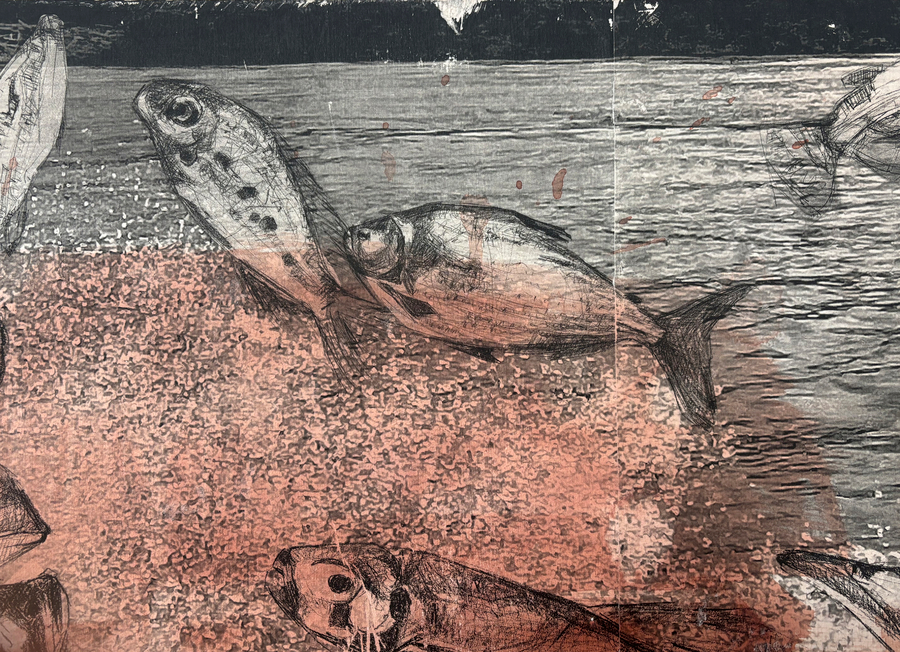

Sandra Brewster, Study for FISH (detail), 2025. Acrylic, photo-based gel transfer on wood. Courtesy of the artist

Sandra Brewster, Study for FISH (detail), 2025. Acrylic, photo-based gel transfer on wood. Courtesy of the artistUsing drawing and photo-based gel-transfer techniques, Toronto-based Sandra Brewster’s installation FISH explores the Essequibo River in Guyana and its distinctive fish species, evoking the fluidity and dynamism of water as a metaphor for migration and transformation. Brewster's work examines the nuanced interplay between identity and environment. Her multidisciplinary practice—spanning drawing, photography, and sculpture—examines the lived experiences of movement and migration, often using gel transfer techniques to create textured, layered surfaces that reflect the unfixed, dynamic nature of diasporic identity. Brewster’s installation offers a transformative, relational perspective on land, water, and history rooted in the diasporic experience.

Now comes the gloaming, for day will end, and the stream, its flow stilled and gathered up, so that trees growing firmly on its banks, their barks white, their trunks bent, their branches covered with leaves and reaching up, up, are reflected in the depths, awaits the eye, the hand, the foot that shall then give all this a meaning.

—Jamaica Kincaid, “At the Bottom of the River”

The Essequibo River stretches more than a thousand kilometres across Guyana. Its source is in the foothills of the Acarai Mountains, located near the Guyana-Brazil border. Its mouth at the Atlantic Ocean lies just twenty-five kilometres west of Georgetown, Guyana’s capital. The character of the Essequibo changes dramatically as it flows northward, in some places the river is shallow and narrow, in others deep and as much as thirty kilometres wide. At times the water moves ferociously through the river’s rapids, while elsewhere it runs still, reflecting the sky like a mirror. The Essequibo is brown in colour, stained by the tannins from leaves that fall from the vast rainforests that surround much of it and the rich silt and sediment in its bed. Its surface is opaque, obscuring from view much of what lies beneath.

Sandra Brewster’s site-specific project FISH dives under the surface of the Essequibo and finds a subject in the diverse freshwater inhabitants of its waters. More than three hundred species of fish live in the Essequibo and its many tributaries, including some sixty endemic species found nowhere else on earth. Using a carefully honed gel transfer technique, Brewster wraps gallery walls in black-and-white photos of the Essequibo. Her delicate process of transferring the images from printed sheets of paper to the wall leaves its traces—folds, tears, shifts, and gaps—which evoke a worn, treasured memento or the incomplete qualities of memory. Brewster’s panoramic vistas are punctuated by gestural drawings of the fish that swim and surge in the dramatic waters of the river. Here, the artist celebrates and honours the diverse life of the river, big and small, native and invasive, predator and prey.

Sandra Brewster, Study for FISH (detail), 2025. Acrylic, photo-based gel transfer on wood. Courtesy of the artist

Sandra Brewster, Study for FISH (detail), 2025. Acrylic, photo-based gel transfer on wood. Courtesy of the artist Sandra Brewster, Study for FISH (detail), 2025. Acrylic, photo-based gel transfer on wood. Courtesy of the artist

Sandra Brewster, Study for FISH (detail), 2025. Acrylic, photo-based gel transfer on wood. Courtesy of the artistBrewster heard about the Essequibo River long before she ever saw it. Described in stories told by her parents, who emigrated from Guyana to Canada in the late 1960s, the river—vast and dark—has become, for Brewster, a rich metaphor. With its many bends, islands, and tributaries, the river is difficult to navigate, and one’s journey on it cannot be fully anticipated or planned. Brewster’s work reveals that these unforeseeable journeys on the Essequibo are not unlike the experiences of those who move from a known place to an unknown one.

Sandra Brewster, Study for FISH (detail), 2025. Acrylic, photo-based gel transfer on wood. Courtesy of the artist

Sandra Brewster, Study for FISH (detail), 2025. Acrylic, photo-based gel transfer on wood. Courtesy of the artistBeneath the surface, however, lies another story. The Essequibo has long provided a rich habitat for the fish that thrive in its murky depths, surging rapids, and silty banks. The fish that live in the Essequibo have adapted to this unique body of water and navigate its idiosyncrasies from below. The water provides their habitat and their sustenance. The fish belong to the river and the river belongs to them.

Essay by John Geoghegan, Associate Curator, Collections and Research, McMichael Canadian Art Collection

Presented by McMichael Canadian Art Collection