Andreas Koch, Let's Stay Friends, 2015, Video Still. Courtesy of the artist.

Andreas Koch, Let's Stay Friends, 2015, Video Still. Courtesy of the artist.Still Film: Photography in Motion showcases three select and very different contemporary positions to show how closely film and video art are interwoven with photography, as forms whose developments influence, build on, and depend upon each other, both technically and conceptually. This group exhibition examines the Goethe-Institut Toronto’s current program arc, “Still Moving,” an exploration of the creative tensions between stillness and movement, safeguarding and changemaking, tradition and innovation.

In video art, which emerged in the 1960s with the growing availability of portable video cameras, photography and film meet in a completely new way. Artists including Nam June Paik, Bruce Nauman, Michael Snow, and Joyce Wieland experimented with the combination of moving image, sound, and space in order to expand the boundaries of traditional forms of expression. Video art adopts the precise image compositions of photography and the narrative and temporal dimensions of film art, but often detaches itself from the linear narrative forms of cinema. Instead, it relies on the fragmentation of time and space, which enables a new kind of perception.

Andreas Koch, Let's Stay Friends, 2015, Video Still. Courtesy of the artist.

Andreas Koch, Let's Stay Friends, 2015, Video Still. Courtesy of the artist. Andreas Koch, Let's Stay Friends, 2015, Video Still. Courtesy of the artist.

Andreas Koch, Let's Stay Friends, 2015, Video Still. Courtesy of the artist. Andreas Koch, Let's Stay Friends, 2015, Video Still. Courtesy of the artist.

Andreas Koch, Let's Stay Friends, 2015, Video Still. Courtesy of the artist.A central aspect of video art is its relationship to reality. Photography is traditionally understood as a testimony to the real, while film creates a more subjective interpretation of reality through editing and montage. Andreas Koch's Lass uns Freunde bleiben (2015) sheds light on the authenticity of the image and plays with the manipulation of time, movement, and identity. A long, purported tracking shot through a typical Berlin pub—Koch's favorite pub, which gives the film its title—creates a loop that ends in itself. The disembodied camera follows a seemingly floating, unstoppable, zooming journey into the pub, out into the night and back again. The boundaries of reality are playfully explored through shifts, cross-fades, double exposures, and offsets in scale. Cacophonous snippets of conversation between the bar’s patrons—including artists and curators—simultaneously penetrate and comment on the visual presence of reality in an ironic and surprising way.

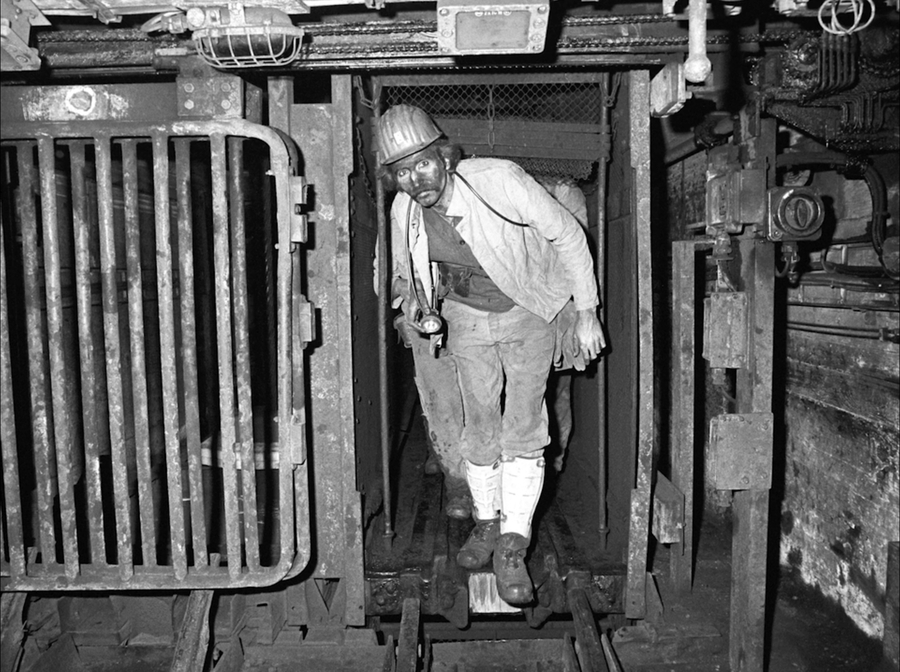

Analogue photography plays a central role in the relationship between photography, film, and video art, especially in the context of documentary and essayistic films such as Pınar Öğrenci's Good Luck in Germany (2024). Analogue photographs, taken from personal collections or, as here, from the archives of the Ruhrmuseum Essen, serve not only as visual material but also as temporal and emotional anchors. In an off-screen voiceover, Öğrenci tells the migration story of exploitation and marginalization of the first Turkish guest workers in West German mining in the post-war period. The montaged images serve as a narrative element that conveys authenticity with its haptics and patina, and creates a connection between individual memory and collective history, or historical omission.

Pınar Öğrenci, Good Luck in Germany, 2024, Video Still. Courtesy of the artist.

Pınar Öğrenci, Good Luck in Germany, 2024, Video Still. Courtesy of the artist. Pınar Öğrenci, Good Luck in Germany, 2024, Video Still. Courtesy of the artist.

Pınar Öğrenci, Good Luck in Germany, 2024, Video Still. Courtesy of the artist. Pınar Öğrenci, Good Luck in Germany, 2024, Video Still. Courtesy of the artist.

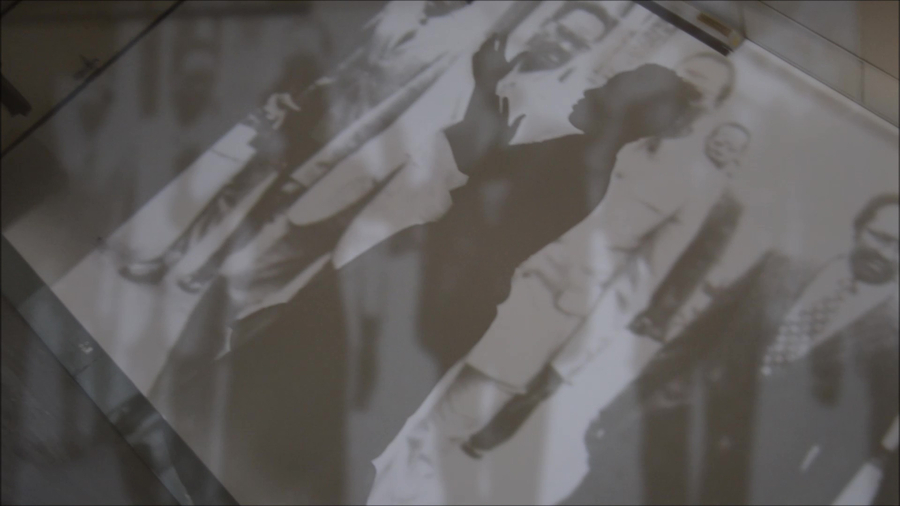

Pınar Öğrenci, Good Luck in Germany, 2024, Video Still. Courtesy of the artist.A performative engagement with photography, as seen in Helena Uambembe's work Do You Hear Me (2018), adds a physical and immediate dimension to the role of photography in the essayistic film or exhibition context. Here, photography is not only viewed but actively staged, questioned, and transformed, making it part of a process that negotiates memory and identity. In her works, Uambembe addresses her personal and familial history as well as the history of the 32 Battalion, and the former South African Foreign Military, in which her father served during the Angolan civil war and the post-war period, with all the associated traumas. After the 1998 disbanding of the 32 Battalion, a secret military settlement was established in the northwest of South Africa, where her parents were resettled, in the middle of the desert, far from their home.

In Do You Hear Me, Uambembe physically intervenes in a photograph’s design and impact by acting in front of a larger-than-life archival image of the Angolan revolutionary leaders Jonas Savimbi, Agostinho Neto, and Holden Roberto. On the occasion of Angola's declaration of independence from Portugal in 1975, these politicians, who later became enemies during the civil war, still appear together. By inserting her shadow into this supposed unity as the protagonists vie for our attention, Uambembe creates an agonizing image that stands for millions of Angolans who suffered the consequences of the war that lasted 27 years and cost between 500,000 and one million lives. Photography is not presented here as a finished artifact of the past, but as a living medium activated and questioned in the present. The performer lends the photographs new meaning by directly incorporating her own physicality and subjectivity. Uambembe's approach in particular stands in contrast to the traditional view of photography as a static medium that conveys an objective or definitive truth. Rather, she shows that photographs are always embedded in narrative, cultural, and political contexts, that they are not only historical traces but also carriers of power relations and collective memories. Her performative practice reminds us that looking at photographs is not only an intellectual act, but also a physical and emotional experience.

Helena Uambembe, Can you hear me, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

Helena Uambembe, Can you hear me, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.Despite the diversity of approaches, the exhibited positions of these artists living and working in Berlin are united by a central motivation: to use photography in the medium of film or video as a tool, to make the complex layers of memory, identity, and reality visible. Whether as a historical document, aesthetic reflection, or performative gesture, photography always functions as a catalyst for dialogue between past and present, individual and society. It invites us to reflect on the relationship between image and time, between personal experience and collective history. There is an essential power in this commonality: the blending of photography and film opens up a space in which the familiar can be questioned and the invisible made visible—a space that invites us not only to see, but also to reflect and feel.

Essay by Olaf Stüber

Presented by the Goethe-Institut with Vtape

Curated by Jutta Brendemühl